Neonatal Surgery

Nicole De Silva, NP

The material presented here was first published in the Residents’ Handbook of Neonatology, 3rd edition, and is reproduced here with permission from PMPH USA, Ltd. of New Haven, Connecticut and Cary, North Carolina.

General Surgical Conditions

Esophageal Atresia ± Tracheoesophageal Fistula

Failure of complete separation of trachea from esophagus results in a variety of tracheal and/or esophageal defects: atresias, stenosis, fistulas, and rarely clefts (laryngeal/tracheal).

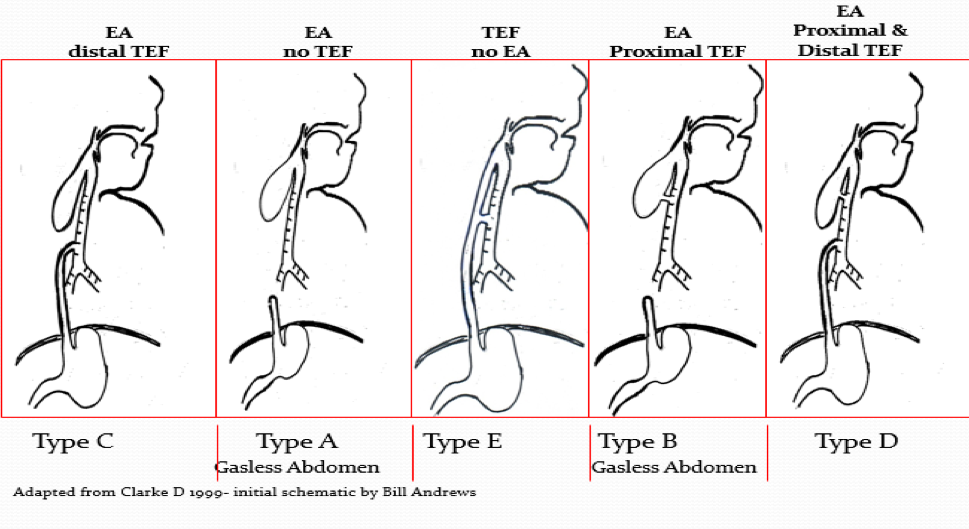

The following are the types of defects according to frequency:

- Esophageal atresia (EA) and distal Tracheoesophageal fistula (TEF) Type C (~85%)

- Esophageal atresia (EA) Type A (~8%) NO proximal or fistula

- Tracheoesophageal fistula (TEF) NO esophageal atresia Type E (~4-5%)- aka “H” type fistula

- Esophageal atresia (EA) with proximal Tracheoesophageal fistula (TEF) Type B (~1%)

- Esophageal atresia with distal and proximal Tracheoesophageal Fistula (TEF) Type D (~1%)

Associations

- Polyhydramnios/no stomach seen on antenatal scans

- Preterm birth

- Small for gestational age

- Trisomy-or other genetic defects-(e.g., CHARGE, Feingold syndrome)

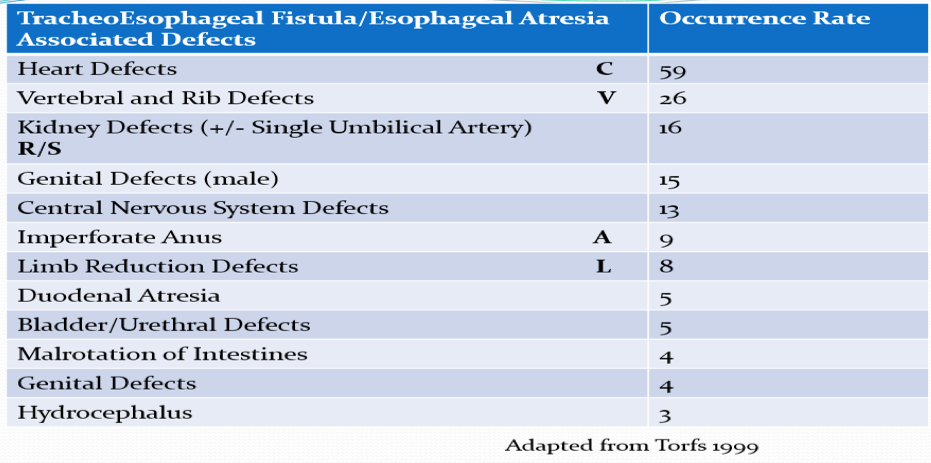

- Other anomalies (50%): i.e., VACTERL association

- Vertebral-spine and spinal cord defects

- Anorectal malformation and other GI anomalies (intestinal atresia, rotational anomalies)

- Cardiovascular (e.g., ASD, VSD)

- Renal and genitourinary (hypospadias and undescended testis)

- Limb

- Other (e.g., lung agenesis or hypoplasia, hydrocephalus, single umbilical artery)

Esophageal Atresia with fistula Type C or D – (proximal or both proximal and distal fistula)

- Presentation: excessive oral secretions, apneic episodes, feeding intolerance (hx of polyhydramnios)

- Diagnosis: as soon as suspected, by passing a radiopaque tube ( 7-8cm in premature infants, up to 10-12 cm in full term infants) into blind upper esophageal pouch. If choanal atresia coexists, the tube can be passed by mouth.

- Prematurity (50%)

- Other anomalies (50%)

Pre OP Management

Replogle ®: # 8 or #10 to continuous suction (use enough pressure until secretions are visible in tube), with instillation of air into secondary (blue port), or ~1ml H2O (only if no proximal fistula is present)

Airway: avoid excessive NIV/bagging-Intubation only as necessary (lowest pressures possible); Assess for “bubbling” of oral secretions/“puffing” of cheeks in synchrony with ventilator breaths-may be a sign of a proximal fistula!

Fluid and electrolyte balance: Establish IV access and provide IV maintenance fluids (consider UVC if no bowel obstruction suspected)

Patient Transport: Once Replogle in place may nurse with head of bed up to decrease gastroesophageal reflux (stomach contents into lung bed via the fistula) If there is no Replogle or NG cannot be passed then HOB down and prone position to facilitate drainage

On admission a surgical team member will assess the level of the obstruction (assess for “bounce back”) of the Replogle, or order insufflation of the proximal pouch if no pouch evident

Esophageal trauma/False Passage: The NG tube may occasionally cause a false passage; signals include difficult tube insertion, the presence of bloody mucous in the tube and the oropharyngeal area. The esophagus may be edematous due to trauma (i.e., perforation) and not allow passage of the tube more distally. A radiopaque water-soluble esophogram is indicated.

Chest radiograph:

- a) to determine if there is a distal TEF: Chest radiograph will show the NG tube in upper pouch; rarely need to instill contrast material. Gas in abdomen indicates a lower (distal) TEF.

- b) to assess for aspiration pneumonia: The most common site is right upper lobe. Treat promptly with oxygen and antibiotics as needed, and prevent re-aspiration.

- c) CV assessment: heart size, position of aortic arch.

- d) Assess for tracheomalasia: a lateral view to assess the degree of impingement that the pouch exerts on the trachea (include neck in lateral film) –listen to the quality of the cry (i.e., hoarse, croaking).

- e) VACTERL: assessment- verterbral/rib anomalies

Diagnose other anomalies early:

- May require early surgical intervention (e.g., CVS, other GI)

- Also, for identification of syndromes and establishment of prognosis (e.g., skeletal, GU)

- Genetics screening if dysmorphic

Timing of surgery: If there is need for CPAP, Ventilation, or a distal GI obstruction (ARM, duodenal atresia), surgery is planned for ASAP due to the risk of gastric perforation

Problems of delayed surgery:

- Over distended stomach/gastric perforation

- -Gastroduodenal contents reflux into distal esophagus, through the TEF and into the tracheobronchial tree, risk of bile or acid injury to pulmonary bed (antacid may be required, pH of ETT secretions ~2).

Management of problems associated with delay in surgery:

- Gastrostomy will help only as a means of gastric decompression (not for feeding)-vent and drain only

- If still unsatisfactory (bile refluxes into the distal esophagus and into airway), transthoracic ligation and ligation of the TEF eliminates pulmonary soiling and allows the institution of gastrostomy feeds.

- A big fistula will allow a large amount of air to enter the stomach-a preliminary gastrostomy may be necessary to avoid gastric perforation (especially if there is a bowel obstruction)

Perioperative Care

- Echo to determine position of aortic arch and any CHD (review fetal echo if available)

- Labs (pre op standard labs

- Initiate VACTERL work up

- Anesthesia (+/- Cardiac Anesthesia) and ENT consults

- Inform parents of any diagnostic findings, diagnoses, operative plan/consent

Surgery

- Timing of surgery: It is rarely necessary (and probably unwise) to embark on primary repair of EA and TEF after hours/overnight unless gastric perforation is imminent or bowel obstruction present

- Emergency surgery: Emergency gastrostomy may be indicated to prevent or treat gastric perforation.

- Perioperative-Rigid Bronchoscopy:

- A ridged bronchoscopy is done in each case to identify a proximal fistula and or distal fistula or any clefts

- The proximal fistula may be very small (a “dimple”) and may be missed on first pass as it is often located just below the vocal cords

- The distal fistula is usually just above the carina

Surgical principles:

may be done open –right posterior lateral incision (4th IC space) or thorascopically (influenced by size and stability)

- First, the fistula is identified, divided/ligated and the trachea repaired (a few sutures usually just above carina).

- The ETT is often advanced to the carina or beyond before the repair then pulled back post repair to sit just above the carina

- Second, the proximal pouch must be identified, bluntly separated from surrounding tissues, pulled down and then anastomosed to the distal fistula (primary anastomosis)

- Any gap greater than 2-3 cm “long gap” increases the technical difficulty and the associated postoperative morbidities

- If the repair is considered to be “tight or under significant tension” the surgeon may request muscle relaxation and sedation to occur along with “chin to chest” positioning for several days post op

- Other conditions may preclude primary anastomosis of the 2 esophageal ends after ligation of TEF:

- Significant respiratory issues (Meconium Aspiration/PPHN), intra-operative events

- Sepsis

- Long gap (>2-3 vertebral bodies)

- Injured or friable upper pouch

Post-Op Care

- CXR to check position of the ETT – confirm with surgery the preferred location of the tip of the ETT

- Suction depth within the ETT only (suction catheter beyond the bevel of the ETT my disrupt the tracheal repair)

- Oral/nasal suctioning should be done to prevent aspiration (anastomosis may be edematous) and oral secretions may not readily pass through the anastomosis

- The depth of oral suction is suggested/ordered by the surgeon (usually no more than 7-8cm)

- A posterior chest drain may be placed if the anastomosis is under tension/tight if the risk of a leak is high. Observe for saliva “frothy bubbles” in chest tube by day 3-5 (when anastomotic edema is resolved, the leak may be evident)

- A small pneumothorax is often evident, and should resorb-the surgeon will place the anterior chest tube for pneumothorax if clinically indicated

AXR

to check position of the TAT

- Often a 6-8Fr TransAnastomotic tube (TAT) is placed through the esophageal anastomosis by the anesthetist into the stomach (the tip of the tube is not visible during the surgery).

- Check the oral cavity for coiling of the TAT in the mouth, pharynx immediately post op

- The AXR will identify the position of the TAT (may be in esophagus, stomach, or post pyloric)

- Consult with the surgeon if the TAT remains in the esophagus (tube may be snagged by a suture) DO NOT ADVANCE OR REMOVE THE TUBE WITHOUT SURGICAL INPUT)- may need to be advanced under fluoroscopy

- The TAT is used for feeding if the tip is in the stomach or post pyloric once bowel function returns post operatively. Feeds can be given continuously (slow drip) or low volume bolus feeds

- IV Antacid is prescribed to protect the anastomosis from acid reflux (prevent scarring)

Safety/Pain Control

- Narcotic Infusion is recommended (see The Hospital for Sick Children’s Guidelines for Pain Assessment and Management)

- Restraints-accidental loss of the ETT and the TAT pose significant risk to tracheal repair and the anastomosis

- Appropriate soft wrist restraints, pain control, and sedation is warranted to prevent agitation

Recovery

The risk of injury to the trachea or the esophagus is heightened during reintubation and “bagging”. Careful consideration is required when planning extubation (SBT passed, need for ongoing narcotic support, prematurity) especially if the anastomosis is under tension/tight.

- Any deterioration post extubating required an immediate CXR and communication with general surgery

- Ongoing “spells”, inability to extubate or wean ventilation my indicate a “missed” proximal fistula or recurrent fistula or leak (contrast/esophogram may be required)

If the anastomosis is felt to be tight/under tension the surgeon may request an esophogram to assess for frank or radiographic leak prior to oral feeding.

Post op Oral Feeding

- If no complications develop during the first week (sepsis, feeding intolerance, “spells” or signs of esophageal leak, need for ongoing ventilation), oral feeding may begin or as per surgical team

- an OT consult is recommended for the first feed if there is significant tracheomalacia suspected- there is a risk of recurrent laryngeal nerve injury resulting in vocal cord paresis/paralysis that will influence the ability to safely feed orally!!!

- Once the child can take full feeds by mouth the TAT may be removed

- If the TAT needs to be replaced discuss the need for replacement under fluoroscopy vs bedside with the surgeon

- In most cases the full term infants go home feeding normally a few weeks after repair of the EA and TEF ligation.

Complication: Anastomotic Leak

Presentation. Leaking at the anastomosis usually occur day 3-5 post op and present with tachypnea, cyanosis, symptoms of sepsis. Chest radiograph typically shows a right pyopneumothorax, pneumomediastinem, and/or effusion. Any of these signs may occur with disruption of the esophagus or tracheal repair post intubation and or mask NIV/bagging.

Treatment

- Intubation/ventilation, if needed

- Broad spectrum antibiotics

- Chest tube may be required for adequate drainage.

- Complete disruption may require surgery (very rare as adhesive changes may complicate thoracotomy).

- Less severe clinical or radiological leaks should be reassessed by an esophagography as needed, indicated before oral feeding as needed

- Nutrition is maintained by tube feeds or TPN until the leak has closed, as determined both clinically and radiologically.

- Many EA anastomotic leaks produce strictures. Thirty to 40% of strictures are symptomatic (with coughing, regurgitation, aspiration, and failure to gain weight). Confirm by esophagography or esophagoscopy, or both.

- Esophageal dilation is done under GA in IGT. It is rare to have to resect a persistent strictured EA anastomosis.

Long-Term Outlook

- Dysphagia: care must be taken when introducing solid foods, until the child understands that he or she will always have to chew food well, eat slowly, and drink frequently during meals.

- Gastroesophageal reflux may be severe enough to require antireflux surgery.

- Tracheomalacia: The more easily collapsible trachea adds to this problem and also accounts for the brassy, duck like cough in these infants. Mild / moderate cases resolve with time. Severe cases cause death. Spells especially postprandial require treatment –aortopexy, tracheal stent

- The survival rate decreases proportionately with the presence of additional defects: >90% if isolated TEF, 75% survival with one additional anomaly and 60% survival with more than one. The cardiovascular defects seem to be the most important determinants of survival.

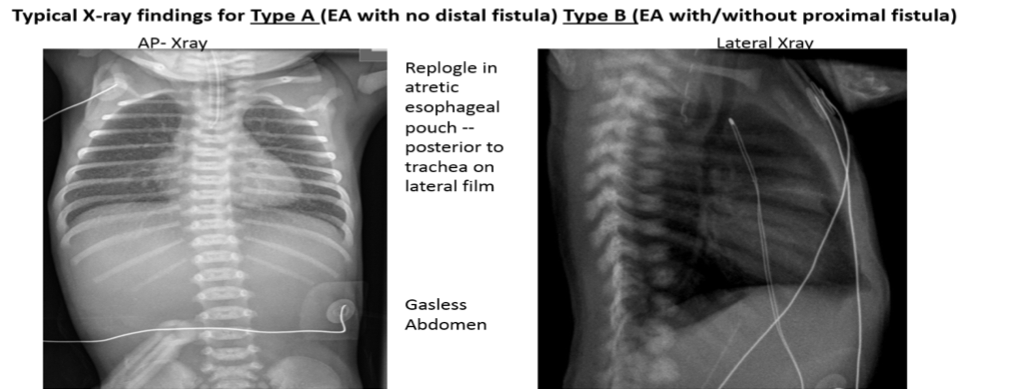

ESOPHAGEAL ATRESIA Type A- NO distal or proximal fistula – (10% of EAs)

- Prematurity (40%).

- Other anomalies (50%):

- 20% have Down syndrome

- Coexisting distal intestinal atresias (e.g., duodenal atresia) are masked by absence of intestinal gas.

- Fewer CVS anomalies than EA + TEFtables

- More skeletal and other GI anomalies than EA + TEF

- Esophageal gap: usually wide

- Site of fistula: there is no proximal or distal fistula (shown by absence of abdominal gas)

- Presentation: excessive oral secretions, apneic episodes, feeding intolerance (vomiting).

- May be misdiagnosed i.e., EA + proximal TEF (Type B) presents with similar x-ray findings!

Management

Replogle ®: # 8 or #10 to continuous suction (use enough pressure until secretions are visible in tube), with instillation of air into secondary (blue port), or ~1ml H2O (only if no proximal fistula is present)

Airway: avoid excessive NIV/bagging-Intubation only as necessary (lowest pressures possible); Assess for “bubbling” of oral secretions/“puffing” of cheeks in synchrony with ventilator breaths-may be a sign of a proximal fistula

Fluid and electrolyte balance: Establish IV access and provide IV maintenance fluids (consider UVC if no bowel obstruction suspected), if gap is wide and suction is long term, hypochloremia may be encountered and routine monitoring of electrolytes is suggested

Patient Transport: Once Replogle in place may nurse with head of bed up to decrease gastroesophageal reflux (stomach contents into lung bed via the fistul a) If there is no Replogle or NG cannot be passed then HOB down and prone position to facilitate drainage

Chest radiograph:

- a) to assess for aspiration pneumonia: The most common site is right upper lobe. Treat promptly with oxygen and antibiotics as needed, and prevent re-aspiration (appropriate oral suction and Replogle maintenance) until repaired.

- b) CV assessment: heart size, position of aortic arch.

- c) Assess for tracheomalasia: a lateral view to assess the degree of impingement that the pouch exerts on the trachea (include neck in lateral film) –listen to the quality of the cry (i.e., hoarse, croaking).

- d) VACTERL assessment: verterbral/rib anomalies

Rarely need to instill contrast material to assess for proximal fistula

Aspiration pneumonia: May be frequent due to overflow of the pouch, malfunctioning of the Replogle

Placement of feeding gastrostomy within the first few days/weeks of life (Prematurity)

- Difficulties occur with the appropriate size Gtube due to the very small stomach and the size of the premature infant (Urinary catheters-6Fr Foley 8Fr-10Fr Malecot used as “off label” Gastrostomy tubes)

- A ridged bronchoscopy is done prior to placement of the gastrostomy tube to rule out proximal fistula,

- if a proximal fistula is identified, it is ligated via a right supraclavicular (neck) approach (precautions to avoid accidental dislodgement of the ETT post op, and avoid use of CPAP)

- Once bowel function returns post Gtube placement, slow drip/continuous feeds are started and eventually ramped up to bolus feeds to “stretch the stomach” !Caution the stomach may be thin and friable/monitor closely for signs of peritonitis after feeds are started

Timing of reconstructive surgery:

- Early reconstruction is seldom feasible owing to wide gap; 75% will come together by 3 months or when birth weight doubles.

- If the gap is 3 cm (three vertebral bodies) or less, a primary repair is possible.

- The distance between the two esophageal pouches is assessed radiologically with a “gap-study” every 4-6 weeks to determine if the gap is shorter

- If the gap stays wider than 3 to 4 cm, the esophagus cannot be united by a primary anastomosis, and the infant will require a gastric pull up, an esophageal replacement: colon, gastric tube, or an esophagostomy (spit valve- extremely rare procedure)

Fokker Technique: Thoracotomy + ligation of fistula. Silk sutures placed in upper and lower esophageal pouches and exteriorized. Sutures pulled daily, stretching esophagus and allowing earlier anastomosis.

Postanastomosis care: Similar to EA with TEF

Long-Term Outlook

- Survival rate in infants with pure EA parallels the rate in the EA and TEF group in that associated anomalies and prematurity tend to lower survival.

- Almost all the children with no other significant anomalies are within two standard deviations of the mean in height and weight.

- Sixty to 70% are without symptoms; the others have only minor complaints (dysphagia with solids, severe reflux or thoracic skeletal deformity).

Tracheoesophageal Fistula (No EA) Type E fistula (aka H-type fisula)

- Diagnosis is may be delayed beyond the perinatal period (especially if only fed by NG)

- Other anomalies are seldom present.

- Presentation: cough, cysnosis, desaturation with oral feeds/fluids

- Can, and does, exist in preterm infants and may present with recurrent pulmonary aspiration episodes while the infant is still in the NICU-more pronounced spells/episodes of “pneumonia” as oral feeding is initiated

- Should be excluded in infant with persistent pneumonia or recurrent “milk” in ETT.

- Diagnosis with UGI or classically “pull-back esophagram” with baby in prone position

- Surgical approach through right supraclavialar incision

Long-Term Outlook

- In spite of normal esophageal motility, some infants have pharyngoesophageal dyskinesia with bouts of aspiration pneumonia.

Congenital Diaphragmatic Hernia (CDH)

- CDH is a defect in closure of the diaphragm, which allows herniation of abdominal viscera into the ipsilateral thoracic cavity. Lung growth and development may be severely compromised, resulting in pulmonary hypoplasia and difficult neonatal adaptation.

- 80% of hernias are left-sided.

- Incidence is approx. 1:4,000 life births and 50% have associated anomalies

Go to the Canadian Association of Pediatric Surgeons publication by the Canadian CDH Collaborative for a detailed guideline for the management of infants with CDH

https://caps.ca/research-and-education/canadian-cdh-collaborative

Antenatal diagnosis

Cases may present with polyhydramnios, or antenatal ultrasound shows abdominal contents in the thorax. In some cases a fetal MRI is done to differentiate between an eventration versus a diaphragmatic hernia. Cases should be referred to a tertiary centre for further investigation and planned delivery in a high risk maternal infant centre. Immediate surgical consult/transfer to a pediatric surgical centre is necessary. The majority of infants are cared for in the PICU. The premature infant/very low birth weight population with CDH are often referred to the NICU for care. An immediate consult to the pediatric intensivist (PICU) is highly recommended. Issues with the risk of IVH,NEC, RDS, PDA/pulmonary hemorrhage, and the evolution of chronic lung disease whilst awaiting surgical repair may present and complicate the course of the premature infant with CDH.

Post natal Presentation

The majority (95%) of infants present with respiratory distress in the delivery room, the others later in infancy or childhood (cough, “chest cold” symptoms). Clinical examination shows a scaphoid abdomen, absence of breath sounds on the ipsilateral side and heart sounds displaced to the contralateral side.

- A CXR (place N/G tube first) is usually diagnostic showing air filled bowel loops or stomach within the thorax

Respiratory Management

- Intubate rapidly after delivery AND avoid bag/ mask ventilation

- Place a large bore NG tube (8-10 French) and attach to low intermittent suction, continuous if there is any emesis.

- Aim to allow for spontaneous ventilation, “gentle ventilation”

- Sedation with narcotic infusion (morphine/fentanyl) is recommended as needed, and muscle relaxation should be avoided if possible.

- Place arterial line for blood gas monitoring and intravenous for fluid and electrolyte therapy.

- Goal is permissive hypercarbia. If peak inspiratory pressures of >30cm H2O are required or hypoxemia or respiratory or metabolic acidosis persist, other methods of ventilatory support should be considered, e.g. HFO. Surfactant use in term infants along with Inhaled NO and ECMO are usually ineffective. Surfactant in premature infants must be considered

- Infants with CDH may have associated pulmonary arterial hypoplasia and are at high risk of developing persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn (PPHN) and baseline Echocardiograms are suggested

Surgical Repair

- Surgical repair is delayed until the infant is stabilized and achieves a weight/gestational age criteria

- Repair is usually carried out through a subcostal incision on the side of the defect; a prosthetic patch may be required for the diaphragm.

Outcome

- Survival rates of 80-90% are reported in many centres, and decreased survival rates for premature and very low birth weight infants as expected.

- Late sequelae include chronic lung disease, severe reflux, reactive airway disease and bronchiectasis.

- All infants should receive close neuro-developmental follow up and hearing assessments.

Abdominal Wall Defects

The most common abdominal wall defects are:

- Gastroschisis

- Omphalocele

Cloacal Extrophy and Cloaca are more rare.

All may have abnormal intestinal rotation / fixation (SMA/V inversion on ultrasound).

Antenatal Diagnosis

Most abdominal wall defects are diagnosed antenatally and referral made to a high risk perinatal centre.

Gastroschisis

- Full thickness of AWD. Usually to right of umbilicus. Usually no other anomalies or genetic abnormalities. Common to have young mother. There is note of an increased incidence across North America and Europe. Gastroschisis may be complex (associated with atresia, necrosis) or simple and the outcomes vary tremendously between the two.

Delivery

Usually planned in a prenatal center; no evidence that caesarean section produces better survival than vaginal delivery at 36-37wks. If the liquor is green at delivery, it may be bile staining vs meconium passed per rectum. If meconium is present suspect bowel perforation if no respiratory/CVS issues at delivery (no evidence of meconium aspiration).

Immediate post-delivery-stabilization/resuscitation

- NGT #8/#10 to low intermittent suction. Replace NG losses with NS+ 20mEqKCl/L 1:1.

- Keep baby warm (to avoid rapid heat loss) (warming mattress and infant centre with over bed heater)

- Centralized bowel loops and wrap the bowel with warm saline-soaked non-woven or Telfa ® sponges, followed by plastic wrap that is covered by gauze wrap “kling”. A large bore NG may be placed within the sponges (under the plastic wrap) to allow for ongoing soaking with warm saline.

- Place baby on right side to prevent bowel mesentery from kinking and thereby, causing gut ischemia

- High volume intravenous fluids (twice maintenance ~100-120ml/kg/day is initiated)

- An initial fluid bolus (10-20mL/kg) may be required if there is any sign of hypotension/hypoperfusion

- Blood cultures as indicated, antibiotics (Ampicillin, tobramycin). Flagyl may be added if bowel ie ischemic/there is a risk of perforaiton

- A common error is thinking that the bowel is nonviable because of its dark color from meconium within the lumen and the occasional meconium staining of its thickened and edematous serosa and mesentery. There is a standard scoring system for “matting” or fibrin deposition, and for the presence of atresia/obstruction, and ischemic injury

- Upon admission to SickKids, the surgeon carefully examines the bowel for matting, signs of atresia, necrosis.

- Vanishing gastroschisis occurs rarely (defect closed/closing, leaving only a small nubbing of bowel

See the link below for the Canadian Association of Pediatric Surgeons Network CAPSNet documents on the scoring of bowel injury for gastroschisis.

See the SickKids NICU Guidelines for Gastroschisis Management

Education for the GS Bowel Injury Score

The Gastroschisis (GS) bowel injury severity score is a composite scoring tool applied to the bowel of GS patients at birth and at each attempted abdominal closure.

The scored variables include:

- Bowel matting: None, mild or severe

- Bowel necrosis: Absent, focal or diffuse

- Bowel atresia: Absent, suspected or present

- Bowel perforation: Absent or present

Below, please see a text description and photographic examples of “bowel matting”. Clicking on an image will display a larger version.

No Matting

Bowel is essentially normal: pliable, soft, not thickened; minimal fibrin formation on surface. No intestinal or mesenteric foreshortening.

|

|

|

|

Mild Matting

Serosal surface is dull (i.e. not shiny); moderate fibrin “peel”, mostly non-adherent. Some thickening with loss of pliability in both bowel wall and mesentery. Bowel loops adherent to each other but separable. Some intestinal foreshortening may be present.

|

|

|

|

Severe Matting

Marked bowel wall thickening, non-pliability. Bowel loops “congealed” with one another. May be difficult to trace individual loops. Abundant fibrin which is quite adherent. Variable bowel discoloration (white/purplish red). Marked intestinal and mesenteric foreshortening.

|

|

|

|

|

Application of Silo and Bedside Reductions

- The usual approach is the placement of a commercially prepared spring loaded silo (Bentec silo) at the bedside with the use of sucrose and narcotic bolus (caution intubation may be needed for placement and reduction of the silo). CXR/AXR is needed to check the position of the ring and the NG tube

- If the silo cannot be placed (bowel too large, defect too small) the procedure will need to be done in the OR under GA (defect may be extended, or a custom made silastic pouch will need to be created and sewn in place to facilitate reduction).

- The Bowel is reduced by the surgical team within 24hrs-once/twice daily (with sucrose or narcotic). The silo is squeezed pushing the bowel into the abdomen a few centimeters at a time and a cotton tie is used to keep the bowel reduced. The bowel may also “self” reduce with the passage of stool

- Close monitoring for signs of ischemia and perforation (green fluid in silo), and decreased perfusion to lower limbs is necessary.

- The bowel may be completely reduced into the abdomen in about 48hrs and ready for closure of the defect

- If the bowel volume is very large and required a hand made silo, reductions may take weeks with longer term ventilation and narcotic use

Closure of the AWD- there is no standard approach to closure of the AWD (Surgeon Dependent) across North AmericaOnce the defect is fully reduced the most common procedures include:

- Plastic/Umbilical Cord Closure: With the use of narcotic and sucrose, the silo is removed at the bedside and the defect is closed using a skin flap or the umbilical cord to cover the bowel and gauze and tape is used to seal/cover the defect (similar to pressure dressing). May be done shortly after admission if the bowel volume is low and complete reduction is facilitated by placement of the silo (rare)

- Operative Closure of the Fascia: Whilst under general anesthesia the silo (spring loaded or hand sewn) is removed. The skin flaps are dissected and attempts are made to close the facia. A gortex patch may be sued (especially if the defect is very large ie hand sewn silo in use). Intra-abdominal-gastric/bladder pressures <20mmHg are acceptable at the time of closure.

Postoperative complications

- Increased intra-abdominal pressure may compress the inferior vena cava, causing lower limb edema/venous congestions and cyanosis. The diaphragm may also be displaced increasing the need for ventilatory support.

- Abdominal wall cellulitis, surgical site infection

- Oliguria

- Persistent metabolic acidosis + lactic acidemia

- Suspect gangrene of bowel in the presence of the three above; this requires urgent re-operation to eviscerate the bowel, check for gangrene, and possible reapplication of a silo

- Signs such as ongoing ileus, dysmotility, failure to advance with feeds may require further investigation (i.e., contrast studies to rule out mechanical obstruction-kink or stricture, vs slow transit time)

Long-Term Outlook

- Postoperative ileus usually lasts a few weeks and in some cases the abnormal pattern of intestinal motility may take months before it reverts to normal so that feedings can be tolerated.

- If the gastrointestinal tract functions normally, the long-term development of the baby with gastroschisis is normal.

- At risk for parental nutrition dependence and intestinal failure with liver cholestasis (an line associated sepsis)

- Currently Gastroschisis is the second leading etiology of neonates referred to the SK intestinal rehabilitation team (GIFT Team).

Omphalocele

- Abdominal wall defect centrally located. Viscera covered in sac (amnion, wharton jelly, peritoneum) with umbilical vessels inserting into sac

- 30-50% assoc. anomalies (eg. CVS) + chromosomal abnormalities

- Fewer fluid and electrolyte abnormalities, and bowel injury if the sac remains intact.

Omphaloceles fall into two rather distinct categories: small and large. They may have a narrow (pedunculated) or wide base. Currently there is no consensus across North America on how to treat/repair a large omphalocele.

Small Omphaloceles

- Prenatal diagnosis occurs for the majority of infants with omphaloceles, followed by a referral to a high risk maternal infant centre for further investigation, surgical consultation, and counseling

- Delivery room staff need to be aware that occasional small omphaloceles are associated with an abnormality of the base (root) of the umbilical cord. If any suspicion exists about the cord anatomy or the contents within the cord, it should be clamped at a distance from the baby to avoid clamping bowel loop(s) within it and a surgical consult obtained

- Small omphaloceles are mushroom or plum-sized protrusions, coming through a fairly small abdominal wall defect, and the saccontains a few loops of bowel

- A significant number of these babies have major chromosomal abnormalities.

- The sac should be wrapped in warm normal saline non-woven gauze, plastic wrap, and kling and transported to a surgical centre (side lying to prevent flopping/kinking)

Surgery

- A twisting procedure is used to reduce the few loops of bowel (usually small bowel) back into the peritoneal cavity, followed by tying the sac and cord at the base.

- Close monitoring for signs of bowel obstruction after the “twist” and reduce method-as a loop of bowel may be inadvertently compromised at the time of reduction/tying off

- If loop(s) of bowel are obviously adherent to the inside of the omphalocele sac, preventing the “twisting procedure,” operative repair is required, to dissect the bowel away from the sac and a fascial closure is achieved. A patch may be necessary to facilitate closure

- If the anatomy of the cord-umbilical area cannot be adequately delineated, operative exploration will be required; this need not be an emergency unless bowel has been inadvertently clamped or cut

- After repair monitoring for any signs of bowel obstruction, intra-abdominal sepsis is necessary

Large Omphaloceles

- Large omphaloceles can be defined as moderately large or very large (potentially larger than the head)

- Relatively few have chromosomal abnormalities.

- Associated major system abnormalities occur in 75% and may have major complications:

- Cardiovascular defects tend to occur with omphalocele of the upper abdomen.

- Genitourinary defects tend to occur with omphalocele of the lower abdomen.

- Babies with huge omphaloceles diagnosed in utero tend to be delivered by caesarean section

- Non-rotation of bowel is the norm with large omphaloceles

- Moderately large omphaloceles have liver and loops of bowel within the rather broad-based omphalocele sac but can almost always be closed within a few days of delivery.

- Incomplete primary repair leaving the neonate with some degree of a skin-covered ventral hernia is quite acceptable; it can be repaired electively and conveniently in the first year of life.

- The size of the base, narrow or wide based can complicate the process of reduction and final closure

Very Large omphaloceles with very wide broad-based abdominal wall defects and huge amniotic sacs containing liver, spleen, and virtually all of the GI tract, pose major problems. These babies have long narrow trunks, occasionally with hypoplastic lungs, and the condition is often complicated by congenital heart disease-ASD and VSD.

- The treatment plan for very large omphaloceles is to cover the amniotic membrane quickly with a temporary moist dressing as described for gastroschisis, prevent drying, cracking or rupture of sac. Side lying is recommended to prevent “flopping” and tearing of the sac

- An intermediate plan for bacteriostatic creams (paint and wait) with Flamazine and gauze (changed daily)

- Prolonged parenteral nutrition may be needed with very large omphaloceles. The position of the stomach and severe reflux affecting respiratory status is a primary problem. Often ND or NJ tubes are required to safely deliver post pyloric feeds (stomach often high in sac, “above” the infant’s head). However, and parenteral nutrition may be necessary for varied periods of time.

- Ruptured omphalocele is an emergency:

- The tear can be sutured and the omphalocele sac preserved if the amniotic membrane is thick enough.

- The torn sac can be removed and a pouch made with foreign prosthesis (usually Silastic material).

- Closure of very large omphaloceles – there are a few alternatives and dependent on associated illness and the width of the base

- To incorporate a small patch of prosthetic material to achieve a temporary closure

- To treat the mound of granulations which replace the sac (amniotic membrane) with some form of near-sterile dressings, which allows ”pseudoskin” to grow up the sides, thereby providing coverage.

1. Attempted early surgical closure using prosthetic material

- The amniotic membrane cover is removed (or left) and then the prosthesis is sewn to the edge of the abdominal wall to create a pouch (silo) which is then covered in as sterile a manner as possible (see below).

- Attempts to reduce (push in) the abdominal contents are carried out in a planned sequence, ranging from daily to weekly, according to the tolerance of the baby and/or the preference of the surgeon. These push-ins can be done quite easily in the incubator with or without sedation, using as sterile as possible a technique.

- If the reductions proceed too aggressively, the prosthetic pouch will separate from its attachment to the abdominal wall, thereby creating further problems.

- Meanwhile, under the prosthesis, the amniotic membrane (if left on) will be replaced with granulations within 3-4 weeks; the same process will also occur if the amniotic sac is removed at the initial operation. If serial reduction is successful, the baby can be returned to the operating room, where, under general anesthesia, the prosthetic pouch is removed and the abdominal wall closed.

- If this fails, ventral hernia is the result, with closure at 1 year.

2. Delayed closure (this commits the baby to a larger ventral hernia)

3. More long term use bacteriostatic/antibacterial products that also contain silver are often used to reduce the bacterial load (colonization) and promote pseudo-skin and decrease the risk of perforation if reduction is predicted to take a lengthy time.

- These babies may require longer term ventilator support due possibly hypoplastic lungs, infection, cardiac defects, increased intra-abdominal pressure.

- Pressure dressing may be applied external to the dressing to gently coax the viscera to reduce into the abdominal cavity

- If there is no progress with reductions, the base of the defect can be widened (if pedunculated) in the operating room, usually with immediate reduction of ventilator support.

- Final repair of this form of ventral hernia is undertaken as described above, at a planned time, usually within the first year or two of life, in one to three stages.

Outcomes vary depending on associated defects (CVS) and the complications during hospitalization (rupture of sac, line infections, aspiration pneumonia, PHTN, ventilator dependence). Fostering growth and development is critical and multidisciplinary team management is essential. Family wellness and coping strategies to manage long term hospitalization is required for successful transition home.

Intestional Obstruction (also see Gastroenterology section)

The common causes of intestinal obstruction in neonates are intestinal atresias, rotational anomalies, meconium ileus, Hirschprung’s disease, and imperforate anus.

- Bilious vomiting in an infant must investigated, and prioritized as a surgical emergency. Delay in diagnosis can result in ischemic injury and loss of the entire gut and likely result in a dismal/fatal outcome.

- All infants require an adequate IV, fluid and electrolyte resuscitation and replacement, and GI decompression via oro/nasogastric tube when intestinal obstruction suspected.

- Radiographs in the neonatal period will not distinguish large and small bowel obstructions and contrast studies will be required.

- The type of contrast studies (upper or lower GI) +/- ultrasound will be determined by the surgeon depending on clinical condition and x-ray findings.

Additional Readings

- Kirpalani, H., Moore, A.M. and Perlman, M., 2007. Residents handbook of neonatology. PMPH-USA

- Dunn JC, Fonkalsrud EW. Improved survival of infants with omphalocele. Am J Surg 1997;173:284-7.

- Ein SH. Esophageal atresia and Tracheoesophageal fistula. In: Wyllie R, Hyams JS, editors. Pediatric gastrointestinal disease: pathophysiology, diagnosis, management. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1993. p. 318-36.

- Engum SA, Grosfeld JL, West KW, et al. Analysis of morbidity and mortality in 227 cases of esophageal atresia and/or Tracheoesophageal fistula over two decades. Arch Surg 1995;130:502-8.

- Devine PC, Malone FD. Noncardiac thoracic anomalies. Clin Perinatol 2000;27:865-899.

- Langer JC. Gastroschisis and omphalocele. Semin Pediatr Surg 1996;5:124-8.