Human Milk and Breastfeeding

Rebecca Hoban, MD MPH

The material presented here was first published in the Residents’ Handbook of Neonatology, 3rd edition, and is reproduced here with permission from PMPH USA, Ltd. of New Haven, Connecticut and Cary, North Carolina.

- Human milk is species-specific and uniquely superior for infant feeding

- Exclusive breastfeeding for term infants is recommended for the first six months of life by the Canadian Paediatric Society (CPS), the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) and the world Health Organization (WHO).

- Exclusive breastfeeding is defined as an infant’s consumption of human milk with no supplementation of any type (no water, no juice, no non-human milk, and no foods) except for vitamins, minerals, and medications.

- Breastfeeding can continue for up to two years and beyond as other foods are added.

Child Health Benefits

Human milk feeding decreases the incidence and/or severity of many infectious diseases including:

- bacterial meningitis

- invasive Haemophilus influenzae type b infection

- diarrhea and gastroenteritis

- respiratory tract infection

- necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC)

- otitis media

- urinary tract infection

- late-onset sepsis in preterm infants

Other Health Outcomes

- decreased rate of post-neonatal death

- decreased rate of sudden infant death syndrome

- reduced incidence of both Type I and Type II diabetes

- decreased incidence of leukemia, lymphoma, and

Hodgkin disease

- decreased rate of obesity, overweight, and hyper-cholesterolemia

- decreased incidence of asthma

Neurodevelopment

- data suggest an enhanced performance on tests of cognitive development in term and preterm infants, but this effect is confounded by social class of mothers

- breastfeeding provides analgesia during minor painful procedures (e.g. heel-stick for blood)

Maternal Health Benefits

- promotes mother and baby bonding

- decreased postpartum bleeding

- lactation amenorrhea decreases menstrual blood loss and may increase child spacing

- earlier return to pre-pregnancy weight

- decreased risk of breast cancer and ovarian cancer

Contraindications to Breastfeeding

- there are very few absolute contraindications to breastfeeding

- breastfeeding is contraindicated in infants with classic galactosemia (galactose 1-phosphate uridyl transferase deficiency) as the infant cannot convert galactose to glucose to prevent severe mental retardation and liver damage and must be fed a galactose-free formula (e.g. Nutramigen)

- breastfeeding is contra-indicated when mothers are receiving diagnostic or therapeutic radioisotopes, or have had exposure to radioactive materials (for as long as there is radioactivity in the milk)

- breastfeeding is contra-indicated for mothers who are receiving certain medications, anti-metabolites or chemotherapeutic agents (Table 1)

- duration of interruption of breastfeeding depends on the drug

- lactation should be maintained with expression

- breastfeeding may be re-established as early as 1-2 maternal drug half-lives following the last dose of most toxic drugs

- breastfeeding may be contraindicated for mothers taking certain “street drugs” (Table 2)

- breast feeding is contra-indicated for mothers with certain infectious diseases (see below)

Maternal Infections and Breastfeeding

Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV)

- In the developed world, HIV positive mothers should not breastfeed

- In developing countries without access to replacement feeding that is acceptable, feasible, affordable, sustainable, and safe (WHO AFASS recommendations), the increased risk of other infectious diseases and nutritional deficiencies with increased infant death rates associated with artificial feeding, outweighs the possible risks of acquiring HIV infection from breastfeeding and improves HIV-free survival, likely with or without maternal anti-retroviral therapy (ART). Exclusive breastfeeding through 6 months and continued breastfeeding until 12 months is recommended.

- In developing settings where breastfeeding is recommended, passive anti-retroviral exposure via breastmilk reduces the risk of HIV transmission.

- Meta-analysis of 11 trials of predominantly breastfed children whose mothers took ART estimated the risk of post-natal HIV transmission through breastfeeding at 1.1% at 6 months and 2.9% at 12 months.

Hepatitis C Virus (HCV)

- Hepatitis C virus RNA and antibody to HCV have been detected in breast milk of infected mothers

- However transmission of HCV via breastfeeding, has not been documented (theoretically possible)

- According to current guidelines, maternal HCV infection is not a contra-indication to breastfeeding (31) but mothers with cracked or bleeding nipples should “pump and dump” their milk and refrain from direct breastfeeding until their nipples heal

Hepatitis B Virus (HBV)

- the risk of an infant acquiring HBV from an infected mother is 70% to 90% without immunoprophylaxis

- perinatal transmission is predominantly from blood exposure during labour and delivery

- although Hepatitis Bepatitis B Virus (HBV) surface antigen (HBsAg) has been detected in milk from HBsAg-positive women, breastfeeding does not significantly increase the risk of infection in their infants

- Infants born to HBsAg-positive mothers should be immunized with vaccine and immune globulin as per schedule. There is no need to delay initiation of breastfeeding until after the infant is immunized (6)

Cytomegalovirus (CMV)

- CMV is ubiquitous and may be transmitted from mother to infant in utero, during delivery, or after birth

- CMV can be isolated from breast milk. Although transmission of CMV through breast milk occurs, symptomatic disease in term infants is rare (probably because of passively acquired maternal antibodies)

- preterm and immunocompromised infants have a greater risk of developing symptomatic disease from CMV in breast milk

- the decision to breastfeed premature infants of CMV positive mothers should weigh benefits of human milk versus CMV risk, but the status of most mothers is unknown to the NICU medical provider

- pasteurization of milk inactivates CMV; freezing to -20°C will decrease viral titers

Tuberculosis

- active untreated tuberculosis is an absolute contra-indication to direct breastfeeding due to a high risk of transmission to the neonate from respiratory tract droplets withclose contact

- mothers should start pumping immediately, and infants can be bottle fed expressed breastmilk by another caregiver – maternal TB treatment medications are safe in lactation. When the mother has been appropriately treated for more than 2 weeks and is no longer contagious she may direct breastfeed (6)

Human T-Lymphotropic Virus Type I and Type II (HTLV-I, HTLV-II)

- HTLV (also known as human T-cell leukemia virus) is a retrovirus associated with malignancies and neurologic disorders in adults

- Studies suggest HTLV-I transmission from mother to infant occurs primarily through breastfeeding.

- Breastfeeding is contraindicated in mothers who are HTLV-I or II positive

Herpes Simplex Virus (HSV)

- cases of transmission of HSV from mothers breast feeding with herpes simplex lesions on a breast have been reported

- breast feeding from a breast with lesions is contraindicated – milk should be pumped and dumped to ensure continued supply

- the infant may feed from the other breast if it is clear, and active lesions on the involved breast and elsewhere are covered; careful hand hygiene must be used

West Nile Virus (WNV)

- WNV is transmitted primarily by the bite of mosquitoes that acquired the virus from infected birds

- WNV transmission in utero has been documented, but infants infected with WNV are asymptomatic or rarely may develop mild disease

- To date only one case of WNV transmission through breast feeding has been documented and the infant remained healthy

- Current recommendations encourage mothers to breast feed even in areas of ongoing WNV transmission (CDC recommendation, 2002)

Zika Virus

- Zika is transmitted primary by the bite of mosquitoes and can have catastrophic effects with in utero transmission

- Zika has been detected in breastmilk from infected mothers, but there are no documented cases of post-natal transmission via breastmilk

- Current recommendations are that benefits likely outweigh the risks and to continue to breastfeed (WHO, 2016)

Rubella

- although wild and vaccine strains of rubella virus have been isolated from breast milk, this has not been associated with significant disease in infants

- women with rubella or women just immunized with live-attenuated rubella vaccine may breast feed

Varicella-Zoster Virus (VZV)

- VSV is a herpesvirus

- A mother with chickenpox or zoster infection does not need to be isolated from her own baby

- Infants of mothers who develop chickenpox within 7 days before delivery or within 28 days after delivery should receive Varicella-Zoster Immune Globulin (VZIG)

- Varicella vaccine may be considered for a susceptible breast feeding mother if the risk of exposure to VZV is high

- Whether varicella vaccine virus is secreted in human milk or whether the virus would infect a breast feeding infant is unknown

- Breast feeding of babies infected with or exposed to VSV is encouraged

Bacteria

- mastitis and breast abscesses may lead to the presence of bacterial pathogens in human milk

- mastitis resolves with continued breast feeding and expression during antibiotic therapy and does not pose a significant risk for the term infant – more frequent breastfeeding or pumping is recommended to reduce symptoms

- breast abscesses are rare (3-5% of mastitis cases) but have the potential to rupture into the ductal system releasing a large number of bacteria, such as staphylococcus aureus into the milk

- feeding from a breast with an abscess is not recommended until the mother is appropriately treated with an antibiotic and the abscess surgically drained

- with an abscess, feeding from the opposite (unaffected) breast should continue and milk from the affected breast should be pumped and dumped

Breast milk banks and donor milk

When direct breastfeeding is not possible (e.g. prematurity)., expressed human milk should be provided Ideally, this should be the mother’s own breast milk.

- Banked human milk is a superior alternative to formula for premature infants whose mothers are unable to provide adequate milk, as it reduces necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC)

- Premature (currently <34 weeks GA at birth at HSC) and other at-risk (ie GI surgical infants) may be fed donor milk with parental consent if mother’s milk is unavailable during the period of highest NEC risk, and are usually weaned off when corrected to late preterm (currently 36 weeks at HSC) or prior to discharge, as it is a costly and limited resource

- Donor milk banking has become common in developed countries. Ontario’s milk bank (Robert Hixon Ontario Human Milk Bank) is in Toronto, based at Mount Sinai.

- Human milk banks must follow strict guidelines for screening and testing of donors, and pasteurize all milk before distribution.

- Donor milk is most often from mothers of formerly term infants who have been lactating many months, so is lower in calories and protein than preterm mother’s own milk. Therefore, although it reduces NEC, it doesn’t usually meet the in-hospital growth requirements of preterm infants, and requires fortification and often the addition of supplemental protein (see fortification section).

The Ten Steps to Successful Breastfeeding

The recommendations below form the basis of the WHO / UNICEF Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative (called the Baby Friendly Initiative in Canada). They are currently the best recommendations to promote breastfeeding in maternity hospitals, and are being modified for paediatric hospitals.

A Joint WHO/UNICEF Statement, Geneva, Switzerland, 1989

Every facility or agency providing maternity services and care of newborn infants should:

- Have a written breastfeeding policy that is routinely communicated to all health care staff.

- Train all health care staff in skills necessary to implement this policy.

- Inform all pregnant women about the benefits and management of breastfeeding.

- Help mothers initiate breastfeeding within a half-hour of birth.

- Show mothers how to breastfeed and how to maintain lactation even if they should be separated from their infants.

- Give newborn infants no food or drink other than breast milk, unless medically indicated.

- Practice rooming-in – allow mothers and infants to remain together 24 hours a day.

- Encourage breastfeeding on demand.

- Give no artificial teats or pacifiers (also called dummies or soothers) to breastfeeding infants.

- Foster the establishment of breastfeeding support groups and refer mothers to them on discharge from the hospital or clinic.

Early postnatal discharge of breastfeeding mothers

Shorter postpartum hospital stays of breastfed infants may increase the incidence of undesirable effects(8) such as

- Dehydration(9)

- malnutrition,

- hyperbilirubinemia

- breastfeeding failure

These may be minimized by establishing adequate breastfeeding frequency postpartum and access to early breastfeeding support following discharge from hospital.

Excellent videos on lactation support are available at the following SickKids and CHEO sites: www.sickkids.ca/breastfeeding-program/videos/index.html

Lactation support for mothers of premature or ill infants

- Mothers who deliver early, as well as mothers who cannot breastfeed their infant directly and are entirely breast pump dependent (aka acutely ill infant with HIE, infant with craniofacial anomalies, etc) are at high risk of compromised and/or delayed lactation

- Early pumping initiation (ideally within an hour of delivery) with a high quality (ideally hospital grade double electric breast pump), frequent pumping (every 3 hours) in the days after birth, and skin-to-skin (kangaroo care) “program” the breast for successful lactation, and are associated with higher milk volumes weeks later

- Early and frequent lactation support is necessary in these mothers to establish and maintain lactation with a breast pump until the infant can feed at breast (if direct breastfeeding is the mother’s goal)

- Early non-nutritive breastfeeding (infant on empty/pumped breast) should be encouraged in premature infants

- Once >32 weeks CGA and off positive pressure, oral feedings may be considered, with starting at the breast optimal. Initiating direct breastfeeding in the NICU is associated with longer lactation periods and less formula supplementation vs exclusive pumping.

- Colostrum, the first milk, is “liquid gold” and high in antibodies and other protective substances, and can be used for oral immune therapy even in infants in the NICU who are NPO

Shorter postpartum hospital stays of breast-fed infants may increase the incidence of undesirable effects such as:

- Dehydration

- Malnutrition,

- Hyperbilirubinemia

- Breast-feeding failure

These may be minimized by establishing adequate breastfeeding frequency postpartum and access to early breastfeeding support following discharge from hospital.

Breast Milk Jaundice

- Differentiate from jaundice caused by an insufficient production or intake of breast milk

- Breast-milk jaundice is an elevation of indirect (unconjugated) bilirubin in thriving breast-fed newborns that occurs after the first 4 to 7 days of life, and can persist for up to 3 months, with no other identifiable cause

- With healthy term infants: Treatment consists of increasing breast-feeding frequency, maximizing breast-feeding support and, if necessary, supplementing with expressed breast milk or formula

- Temporary interruption of breast-feeding is very rarely needed and is no longer recommended

- Supplementation with dextrose solution is not recommended

- Monitor weight and bilirubin levels

- Phototherapy is added as per guidelines

- Prognosis is excellent

Vitamin and Mineral Supplementation of Breastfed Infants

Vitamin D

- vitamin D deficiency may lead to rickets and osteomalacia

- babies are most at risk for vitamin D deficiency if:

- they are exclusively breastfed

- their mothers are vitamin D deficient

- they have darker skin

- they are not exposed to enough sunlight

- they live in northern communities

Canadian Pediatric Society, Dieticians of Canada and Health Canada recommend that all breastfed infants should receive 400 IU of vitamin D daily from birth until one year of age, or until the infant’s diet includes at least 400 IU of vitamin D daily. Infants from northern Native communities should receive 800 IU during winter months.

Iron

- iron deficiency anemia is a risk factor for developmental delay in cognitive function

- exclusive breastfeeding will meet the iron needs of most healthy term infants until 6 months of age

- iron fortified and vitamin C fortified solid foods should be introduced at 6 months

- preterm infants require iron supplements after NICU discharge if exclusively or mostly breastfed until 12 months of age with ELBW (BW <1kg) needing 3-4mg/kg/day and infants with BW ≥1kg needing 2-3mg/kg/day.

- small for gestational age infants, or infants with haematologic disorders, inadequate iron stores or born to iron deficient mothers, may require iron supplementation prior to 6 months if exclusively or mostly breastfed

- infants weaned from breastfeeding prior to 9 months of age should receive iron-fortified formula

- introduction of cow’s milk prior to 9 months may contribute to iron deficiency anemia

Fluoride

- fluoridation of the water supply reduces dental caries

- excessive fluoride intake can cause dental fluorosis

- supplementary fluoride is not recommended during the first 6 months of life

- fluoride supplementation is not recommended if the principal drinking water source contains 0.3 ppm of fluoride

- The Canadian Pediatric Society and Canadian Dental Association recommend that infants between the ages of 6 months and 3 years who live in areas where the water supply contains less than 0.3 ppm fluoride, receive 0.25 mg fluoride daily

Breast milk fortification for preterm infants

- Exclusive feeding of un-fortified human milk has been associated with reduced rates of in-hospital growth in preterm infants, due to the variation in energy and protein content of human milk, increased metabolic needs, and the need for volume restriction in some infants

- Intake of calcium, phosphorus, sodium, vitamins and energy is also often inadequate

- The use of multi-component human milk fortifiers lead to short term improvements in growth and help prevent or treat osteopenia of prematurity. Although limited studies, there is no clear evidence of long term benefits. Various methods of supplementation are currently used in-hospital, including commercially available liquid or powdered bovine-based human milk fortifiers, human milk-based liquid human milk fortifier (Prolacta), and mixing of breast milk with preterm formula (usually reserved for infants who are corrected to term or close to discharge as this many be continued at home). There is no definite evidence that human milk based human milk fortifier is superior to bovine products, so given its higher cost, bovine-based products are currently more commonly used.

Table 1: Drugs Contraindicated in Breastfeeding

| Drug | Effect in Infant |

| Anticancer drugs/ Cytotoxic drugs:

Cyclophosphamide Methotrexate Doxorubicin Cyclosporine |

Possible immune suppression

Effects on growth and carcinogenesis unknown |

| Radioactive compounds:

Gallium 67 Iodine 125 Iodine 131 Technetium 99m |

Radioactivity can remain in milk for variable periods, up to 2 weeks, depending on isotope half-life

Temporary cessation of breastfeeding, continue pumping, but discard while radioactivity present in milk (test sample before resumption) |

| Bromocriptine (Parlodel) | Suppresses lactation in mother

Breastfeeding not possible |

Drugs with known or possible side-effects (use with caution)

| Drug | Side-effect |

|

Ergotamine (migraine therapy) |

May cause vomiting, diarrhea, and convulsions

May suppress lactation |

| Lithium (bipolar disorder therapy) | Limited human data, long term effects unknown

May cause lithium toxicity in infant |

| Isotretinoin (Accutane, acne therapy) | No data, potential toxicity |

| Diazoxide (antihypertensive) | No data, potential toxicity |

| Major Tranquilizers (Neuroleptics):

Chlorpromazine (Thorazine) Haloperidol (Haldol) Clozapin (Clozaril) Risperidone (Risperdal) |

Limited human data, potential toxicity Potential sedation in infant

|

| Minor Tranquilizers (Anxiolytics):

Alprazolam (Xanax) Diazepam (Valium) Lorazepam (Ativan) Midazolam (Versed) |

Limited human data, potential toxicity

May cause infant sedation and weight loss May accumulate in breastfed infants |

| Chlorpropamide (oral hypoglycemic) | Limited human data, potential toxicity

May cause hypoglycemia |

| Chloramphenicol (antibiotic)

|

Limited human data, potential toxicity

Risk of bone marrow depression |

| Misoprostol (Cytotec) | Limited human data, potential toxicity

May cause severe diarrhea in infant |

| Aspirin (salicylate) | Limited human data, potential toxicity with very high doses for long periods

Potential affect on platelet function |

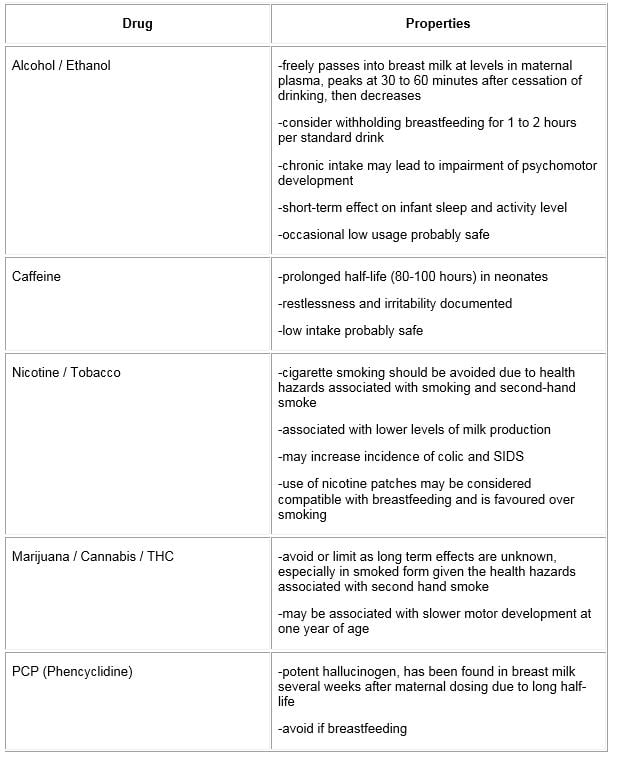

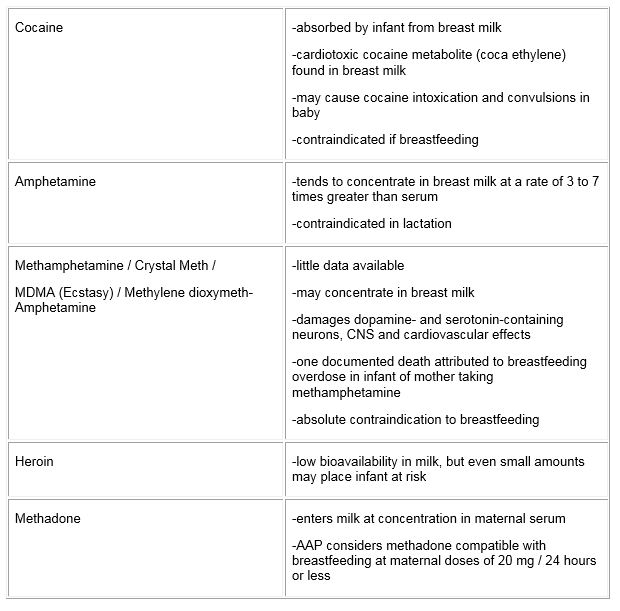

Table 2: Recreational and Illicit Drugs

Additional Reading

A joint statement of Health Canada, Canadian Paediatric Society, Dietitians of Canada, and Breastfeeding Committee for Canada. Nutrition for Healthy Term Infants: Recommendations from birth to six months. Minister of Public Works and Government Services, Ottawa, 2015.

American Academy of Pediatrics. The Transfer of Drugs and Therapeutics into human breast milk: An update on selected topics. HC Sachs, Committee on Drugs. Pediatrics 2013;132;e796.

American Academy of Pediatrics. Transmission of infectious agents via human milk. In: Pickering LK, ed. Red Book: 2015 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. 30th ed. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2015.

Briggs GG, Freeman RK, Yaffe SJ, Drugs in Pregnancy and Lactation: A reference guide to fetal and neonatal risk. 10th edition, Philadelphia, PA: Williams & Wilkins, 2015

Buckle A and Celia T. Cost and Cost-Effectiveness of Donor Human Milk to Prevent Necrotizing Enterocolitis: Systematic Review. Breastfeeding Medicine. 2017(12):9,528-536

Guidelines on HIV and infant feeding 2010: Principles and recommendations for infant feeding in the context of HIV and a summary of evidence” by the World Health Organization

Mortensen EL, Michaelsen KF, Sanders SA, Reinisch JM. The association between duration of breastfeeding and adult intelligence. JAMA 2002;287:2365-2371

WHO Guideline: Protecting, Promoting and Supporting Breastfeeding in Facilities Providing Maternity and Newborn Services. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2017.