Follow-up of the High Risk Neonate

Elizabeth Asztalos, MD, MSc, FRCPC

The material presented here was first published in the Residents’ Handbook of Neonatology, 3rd edition, and is reproduced here with permission from PMPH USA, Ltd. of New Haven, Connecticut and Cary, North Carolina.

Over the past decades, there has been improvements in the management of high-risk pregnancies mostly in the form of the use of antenatal corticosteroids, vaginal progesterone, improved perinatal surveillance e, and timely delivery of high-risk fetuses. Concurrently, neonatal care has also made steady improvements such that very preterm infants at the limits of viability are now surviving the neonatal environment in greater numbers. The very preterm infants is not the only group of infants who benefit from the advances of obstetrical and neonatal advances. Congenital anomalies amenable to surgical intervention both antenatally and postnatally also contribute to improved survival of these infants in the neonatal period. Infants who have experienced hypoxic events perinatally now have greater chance at survival and improved outcomes.

These infants are at risk for long-term adverse neurodevelopmental outcomes due to complications during the perinatal and neonatal period. As such, it is important to ensure there is a mechanism in place to monito r and identify those infants with neurodevelopmental challenges to ensure appropriate supports are put into place post discharge and over the first years into childhood.

The overall goal is to ensure that every child can achieve its fullest potential regardless of limitations that may present themselves and to support the families .

Aims

The aims of any program designed to follow high-risk neonates should include the following:

- Ensure appropriate ongoing care for the neonate following discharge from the neonatal intensive care setting

- Act as a resource for primary care practitioners who are responsible for the care of these infants with acute and chronic need

- Identify neurodevelopmental/ neurosensory difficulties and facilitate appropriate interventions that will optimize the infant’s/child’s developmental pot

- Determine the outcome s of high-risk neonates as an ongoing audit of overall care of these infants. These outcome measures not only serve as a measure of quality assurance but for research purposes as Because outcome can vary from one institution to another, follow-up provides an opportunity to observe results of individual institutional strategies during the neonatal period.

Personnel

Child development is a very complex process .To ensure accurate identification of problems and provide appropriate and adequate support, it is important to ensure that personnel involved be familiar with normal patterns of growth and development of this unique population to recognize abnormal variation .Utilization of individuals from various disciplines becomes crucial in the follow-up program .These disciplines include:

- Developmental clinician s, early childhood practitioners

- Therapists (occupational and physical)

- Speech and language specialists

- Educational specialists (school and behavioral therapists/psychologist s)

- Physicians

- Nurses

- Social workers

- Nutritionists

Not all need to be involved with every child -a core group of individuals are needed to address the bulk of the common difficulties presented and to access remaining resources as needed. Usually the neonatologist/physician in charge of the follow-up program acts as a coordinator of supports and as a support for the family.

Criteria for Follow-up

- Each neonatology program must identify groups of high-risk infants where follow-up is deemed

- In general, some categories of infants are considered essential to most neonatal programs:

- Infants with birthweights s 1000 grams or gestational age <28 weeks (some programs may include for institutional reasons s 1500 grams or gestational age < 30 weeks

- Infants with identified neurologic conditions

- Ventriculomegaly with/without intraventricular hemorrhage

- Periventricular leukomalacia Porencephalic cysts

- Post-hemorrhagic hydrocephalus with/without shunt

- Hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy

- Seizure disorder

- Meningitis/ Central nervous system infection

- Infants receiving high-technology interventions

- ECMO

- Infants with ongoing pulmonary disease

- Bronchopulmonary dysplasia with/without ongoing oxygen need

- Infants needing home oxygen for other reasons

- Infants with tracheostomies

- Infants with ongoing complications in the neonatal period

- Septicemia

- Hypoglycemia

- Hyperbilirubinemia

- Other

- Congenital heart disease

- Feeding difficulties with/without gastrostomy tubes

Outcomes

Terminology

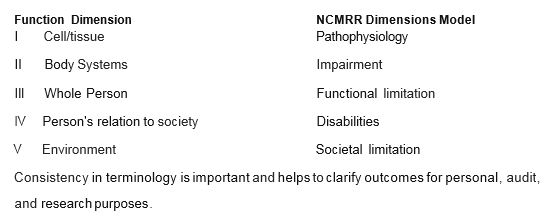

Outcome evaluation can follow several dimensions of function. The National Center for Medical Rehabilitation Research (NCMRR) outlines a model of disablement based on current outcomes research in chronic disease states and is endorsed by the American Academy for Cerebral Palsy and Developmental Medicine. This model provides a framework to assess clinical outcomes and promote appropriate and evidence based developmental support.

Outcomes of Importance in Follow-up: Adverse neurodevelopmental/neurosensory impairments

Identification of major neurodevelopmental/neurosensory impairments is an important measure of the quality of care both institutionally and in general. These can be viewed as the minimal outcome assessments to be gathered for any neonatal program. These outcomes fall into one of three domains:

- Neuromotor abnormality: the most common neuromotor abnormality is cerebral palsy. Cerebral palsy is an umbrella term for a non-progressive motor impairment secondary to injury to areas of the brain which control motor skills. The motor impairment is further categorized as ambulatory and non-ambulatory with the level of function further categorized according to a scoring system such as the Gross Motor Functional Classification System (GMFCS).2

- Neurocognitive abnormality: abnormalities in neurocognitive and language abilities usually are defined from standardized assessments for the young child. These assessments often have standardized scoring systems with various cut-offs to identify various severities of difficulties. The most commonly used assessment has been the Bayley Scales of Infant Development for Infants and Toddlers with the third edition currently being used (Bayley- 111)3;a fourth edition is forthcoming .

- Neurosensory abnormalities: these involve vision and hearing A visual acuity of below 20/200 for any eye suggests significant impairment. A severe hearing impairment: reduced hearing> 40 dB within voice range (250-4000 Hz) without conductive loss, and requiring a method of amplification (aids, cochlear implant).

Neurodevelopmental impairments are further delineated into either being mild or more severe as defined by the table below:

| Impairments | Significant NDI (any one or more of the following) | NDI (any one or more of the \following) |

| Motor | Cerebral Palsy (CP) GMFCS Ill, IV, V. Bayley-III motor composite <70 | CP with GMFCS I or II Bayley-III motor composite

<85 |

| Cognitive | Bayley-III cognitive composite <70 | Bayley-III cognitive composite <85 |

| Language | Bayley-III language composite <70 | Bayley-llI language composite <85 |

| Hearing | Hearing aid or cochlear implant | Sensorineural/mixed hearing

loss |

| Vision | Bilateral visual impairment | Unilateral or bilateral visual impairment |

Methods of identification

How adverse difficulties are identified and managed in any follow-up program is determined by the method of identification. This may be determined by the program criteria and staff resources.

Three levels of identification can be considered and utilized in any given situation:

- surveillance: detection of any developmental problems

- screening: using cost-effective instrument/tools with known specificity, sensitivity, reliability and validity to identify those infants/children with an increased likelihood of having an adverse finding

- assessment :use of standardized measures to confirm the presence of an adverse finding as well as determine the severity.

Timing of assessments

The timing of visits is determined by several factors:

- staff resources

- nature of the high risk population

- type of surveillance used

Ideally, the frequency of visits should capture key developmental milestones or achievements. By convention, prematurity is corrected by subtracting the number of weeks of prematurity from the chronologic age of the child to give an adjusted or “corrected” age until at least the second birthday.

Examples of visit times (corrected age):

- 3-6 weeks

- 4 months

- 8 months

- 12 months

- 18 months/24 months

During these visits, screening or standardized assessments can be employed to determine the presence or absence of major neurodevelopmental/neurosensory outcomes. Common tools have included:

- General Movement Assessments of Infants (GMA)

- Movement Assessments of Infants (MAI)6 Alberta Infant Motor Scale (AIMS)

- Ages and Stages Questionnaire (ASQ)

- Modified Checklist for Autism in Toddlers, revised with follow-up (M-CHAT-R/F)

- Bayley Scale of Infant Development-Ill (Bayley-111)

- Gross Motor Function Classification System (GMFCS)

- Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales

Following 2 years of age, additional screening or standardized assessments are work intensive and require considerable effort on any program.

However, clearer information on functional difficulties is often best obtained after the age of two. With growth and maturity, learning, motor, language and behavior skills are more clearly defined. Should a program choose to continue following children beyond the age of two, various screening or standardized assessments can be employed; it is beyond the scope of this manual to begin listing all the tools available.

References

- National Institute of Research plan for the National Center for Medical Rehabilitation Research . Washington DC: US Department of Health and Human Services, 1993

- Palisano RJ, Rosenbaum P, Bartlett D,Livingston Content validity of the expanded and revised Gross Motor Function Classification System. Dev Med Child Neural 2008; 50(10) :744-750. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2008.03089.x

- Bayley N. Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development-3rd edi San A ntonio, Tx : Psychological Corporation; 2006.

- Synnes A, Luu TM, Moddemann D, Church P,Lee D, Vincer M, Ballantyne M, Majnemer A,Creighton D, Yang J,Sauve R,Saigal S, Shah P, Lee SK; Canadian Neonatal Network and the Canadian Neonatal Follow-Up Network. Determinants of developmental outcomes in a very preterm Canadian cohort . Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2017 May; 102(3): F235-F234. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2016-311228. Epub 2016 Oct 6.

- Sharp M, Coenen A, Amery N. General Movement assessment and motor optimality score in extremely preterm infants Early Hum 2018 Aug 20;124:38-41. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2018.08.006.

- S.Chandler, M.S. Andrews,M.W .Swanson Movement Assessment of Infants:A Manual AH Larson Ed, Washington (1980), pp. 1-52

- van Haastert IC,de Vries LS,Helders PJ, Jongmans Early gross motor development of preterm infants according to the Alberta Infant Motor Scale. J Pediatr. 2006;149:617- 622.

- Squires J , Twombly E,Bricker D, Potter M Ages & Stages Questionnaires ®,Third Edition (ASQ-3™) . Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookes Publishing Co., Inc.; 2009.

- Robins DL, Casagrande K, Barton M, Chen CA, Dumont-Mathieu T, Fein Validation of the modified checklist for Autism in Toddlers, revised with follow-up (M-CHAT-R/F) . Pediatr 2014; 133: 37-45.

- Sparrow SS,Cicchetti DV, Saulnier CA.Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales-3rd edition (Vineland -3). Sa n Anto nio, Tx : Psychological Corporation; 2016.