Ethical Decision-Making in the Health Care of Newborn Infant

Jonathan Hellmann, MBBCH, FCP(SA), MHSc

The material presented here was first published in the Residents’ Handbook of Neonatology, 3rd edition, and is reproduced here with permission from PMPH USA, Ltd. of New Haven, Connecticut and Cary, North Carolina.

This guideline addresses 5 distinct yet interdependent components of decision-making in the NICU:

- The Best Interests Standard of Judgment

- Communication with Parents and Guardians

- A Procedural Framework for Ethical Decision-Making

- Conflict Resolution

- Bioethics Consultation

1. The Best Interests Standard of Judgment

The prevailing standard of judgment for healthcare decisions regarding newborn infants is the young child’s best interests. It is a concept that attempts to ensure that their interests remain the focus of attention and are not overridden by other interests. The rightful decision-makers must make every effort to derive congruency as to what constitutes the best interests of the newborn child. When consensus cannot be easily negotiated, polarization of views among parents, physicians and the healthcare team may lead to great stress and conflict. With a structured, shared decision-making process and a nuanced interpretation of both the value and limits of the best interests standard, as well as an appreciation of the importance of respecting parental authority and the expression of their views and values, a consensual ‘good clinical judgment’ decision is achievable. What establishes moral acceptability for the decision-makers in such interactions is not the application of a moral theory or a purely rationalist argument establishing indubitable first principles, but the clarity arising out of a mutually-derived decision in which all parties have been empowered, their preferences articulated, and where dialogue and negotiation have achieved resolution.

Pursuing a newborn child’s best interests implies determining the potential for the success of the proposed treatment; the risks involved in the treatment; the degree to which the treatment will, if successful, extend life; the pain and discomfort with the proposed treatment; and the anticipated quality of life with and without the treatment (AMA 2010). In assessing best interests a harm/benefit balance is determined in an attempt to maximize benefits and minimize harms in providing care to these patients.

Decisions should be based on the best evidence available. While it is important to acknowledge that medical evidence is not static and that generalized evidence must be interpreted, analysed and applied to the specific patient, via a process of clinical reasoning and scientific and humane judgment (Downie and MacNaughton 2000) and the application of the relevant facts to that specific patient, what is in the patient’s best interests can be determined to support that assessment.

Parents and the young child’s best interests standard of decision making

-

- In most jurisdictions the state recognizes the child’s place within the social unit of the family and confers the responsibility for healthcare decision-making on the parents of young children, as they have a unique relationship with their children, one of concern, obligation, responsibility and intimacy

- There is the presumption that parents will act to promote their child’s best interests and make healthcare decisions in that light

- In the Family-centred model of care (FCC) the family is viewed as a partner in the care of their child and plays a decisive role in ethical decisions. FCC also considers the effects of a decision on all family members, their responsibilities towards one another, and the burdens and benefits for each family member

The Child’s Best Interests Standard of Judgment must address:

-

- How family interests should be incorporated when these differ from what is considered to be in the child’s interests alone

- When what is best may be unknowable due to the difficulty of accurate prognostication

- When a family’s assessment of the child’s best interests is a reflection of cultural diversity

Family Interests

Respecting parental views is a means of equalizing the parental role in decisions with physicians who shape parental views, sometimes even without consciously intending to do so. Physicians need to be conscious of the impact of their authority and the power that derives from their expertise or that follows from information given in a convincing manner. Conversely, in light of the systemic validity attributed to parental authority some physicians may become reluctant to express their own judgment, recommendations or views, particularly when known to be counter to the expressed or even non-expressed views of parents. Physicians’ fear that their assessment of a child’s best interests being interpreted as paternalistic could result in a general hesitancy to engage in interaction about values and preferences with parents. This may lead to a degree of ‘hiding behind’ parental authority or, even more troubling, ‘abandoning’ patients to make their own decisions.

It must also be appreciated that some parents may not wish to make certain decisions for their children and that they should not feel compelled to do so. This is particularly relevant where an end-of-life decision is being considered. The emphasis on parental autonomy may be over-emphasized: Paris et al (2006) and Montello and Lantos suggest that basic human nature may be fundamentally at odds with the emphasis on rationality and autonomy, and that it should be appreciated that “the desire of parents and sometimes of physicians to avoid responsibility for the death of a patient, particularly a newborn infant, can be overwhelming” (Montello and Lantos 2002). Physicians and teams also have to recognize that parents’ ability to reason and to act in a self-directed way is often diminished in the presence of serious illness in their children.

Prognostic Uncertainty

There are many clinical situations in which a child’s best interests may be unclear due to uncertainty about the predictable outcome. Multiple intrinsic factors (individual resiliency, plasticity of response) and extrinsic factors (timing, availability and access to rehabilitation services, socioeconomic factors and social supports) exist that may modulate outcome (Racine and Shevell 2009). Uncertainty and variability are intrinsic to the process of prognostication, rendering best interests assessments inherently complex. In acute situations, and pending clarification of the circumstances, the presumption should normally be in favour of life-saving or life-sustaining treatment (Harrison C, CPS Statement 2004). When it is possible to defer or delay acute treatment, such a delay is encouraged as further information is gathered to clarify any prognostic uncertainty.

Cultural, Religious and Spiritual Dimensions of the Family Pertaining to Decision-Making

The broad acknowledgement of the child’s place within a family often brings out the cultural, religious and spiritual dimensions of the family’s lives. There is a need to recognize, understand and respect these family views and values. Misperceptions caused by a lack of sensitivity can lead to inappropriate care and poor clinical outcomes.

While the healthcare team should recognize how families’ views are shaped by social, cultural and other contexts, it is also important not to stereotype members of specific cultural, ethnic or religious groups. Their backgrounds may not be predictive of their beliefs and values in the care of their child: each patient and family should be considered unique, and their specific views and values acknowledged in an ethical decsison-making process.

Religion and the more general concept of spirituality as a major component of culture, tradition or family values need to be addressed when ethical decision-making is undertaken.

When attentiveness to the views and values of families is difficult because of language barriers, professional interpreters should be used. This ensures that parents’ views are available to the healthcare team, it removes the burden on family members or friends for the transfer of information, and limits the potential for miscommunication. In certain situations a cultural interpreter may not only facilitate language comprehension but also provide useful information about cultural norms and traditions that may be unfamiliar to the healthcare team.

There is the potential for tension in decision-making with parents where a strict adherence to parental decision-making authority may limit the acceptability of their requests or demands for treatment that are not considered to be in the best interests of the young child. What is required is the integration and harmonization of the positive synergy of both these concepts, i.e. the child’s interests and the family’s interests, in a shared decision-making process to avoid conflict when ethically challenging decisions are required.

Despite these challenges to the best interests standard of judgment, it is accepted as the guiding principle for decision-makers. It focuses attention on the child and serves as a powerful tool for settling issues about how to make good decisions for those who cannot decide for themselves. Best interests is not only a standard of judgment but also a standard for possible intervention when it is perceived by the rightful decision-makers (see below) that the child’s best interests are not being served by a particular course of action (Kopelman LM 2005). While it serves as a useful concept in choosing treatment or non-treatment options it does not serve as well in overriding parental wishes, nor does it answer the question of when, if ever, family-centered interests should or could override those of the child.

2. Communication with Patients and Parents

Underlying all components of decision-making is the content and manner of communication with parents. They require information about the diagnosis and prognosis, the available treatment options (including, where relevant, the option of no treatment), the risks and benefits of each option, and the limits of technology. How information is communicated influences their understanding, their ability to discuss issues openly, and their ability to participate effectively in a decision-making process. Transparency in a physician/team’s’ thinking and reasoning helps parents to build an understanding of their child’s condition and tempers unrealistic expectations (King 1992).

It is therefore important to describe the elements of effective communication and the development of a trusting relationship with parents.

General Guidelines

- Create an environment for communication that encourages parents to participate, ask questions, and to be as fully informed as possible

- Identify and remove any barriers that limit parents’ role in communication with regard to their child’s care, e.g. language, physical distance, etc.

- Engage in open, honest and truthful communication at all times

- Provide information as accurately as possible, and with as much certainty of diagnosis and prognosis as is possible in each clinical situation

- Communicate with parents at the time of admission, at any crisis point in the course of the newborn infant, at any time at the request of the parents, as well as regular, periodic reviews of longer stay patients

- Be pre-emptive in communication, i.e. anticipate what problems or issues might arise in the course of that infant

- Keep parents informed of any special investigations planned

- Meet with both parents whenever possible so as to avoid burdening one parent with conveying information to the other

- Ensure parents’ understanding by asking for their questions, and concerns

- Always enquire what parents have been told or understand at the start of a meeting with them

- Use plain language and be mindful of medical terminology and acronyms

- Use diagrams, figures to help understanding

- Be wary of the use of percentages and statistics

- Be aware of your body language and facial expression

- Recognize parents’ need for processing and absorption and often repetition of information

- Encourage information-seeking

- Identify areas of medical uncertainty and explain the concept of prognostic uncertainty

- Assess family communication preferences and attempt to communicate within those parameters, while at the same time explaining limits on the use of social media

- Ensure consistency and continuity in the face of staff changes and handovers

- Determine if inconsistent information is being provided and arrange opportunities to correct interpretations from different sources

- Be sensitive to cultural, religious and spiritual dimensions of the family

- Ask about ethnic identity

- Allow parents to tell their story of the pregnancy and other related life events

- Optimize unstructured opportunities to talk with parents.

- Explore parents’ hopes and fears

- Be proactive in communication in any clinical situation in which a poor outcome can be foreseen

- Convene formal meetings with parents when important decisions need to be made

- Explain the concept of shared decision-making

- Be mindful of the power imbalance in the relationship

- Ask about social supports

- Ask about stresses outside of the biomedical focus, e.g. psychosocial stresses

- Practise open, honest and timely disclosure regarding medical error

- Accept that you have biases and develop the capacity to observe yourself in action

- Try to interact and learn about parents toward whom you may have bias

- Do not stereotype parents of diverse cultures, remember each family has a unique culture

- Address diversity directly

- Listen, listen, listen

- Remember the locus of your humanity is in the parent – provider relationship

- Be aware of the circumstances in which the interaction is taking place.

Develop an informal ‘communication contract’ with parents,

one in which it is conveyed that the team/responsible physician will commit to a number of elements of communication in return for the expectation that parents will inform the team of any misunderstanding, disagreement with assessment or plans or any other concerns

Spectrum of Communication

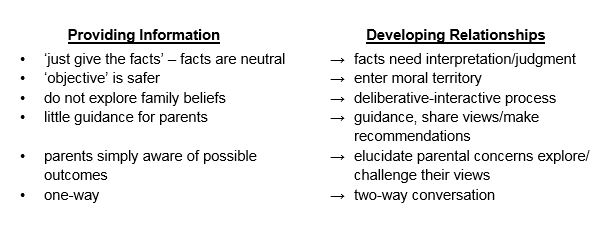

It is critical to appreciate the difference in communication when implemented as an information- providing process as opposed to when the intention is to develop a relationship with the parents. In the former mode the responsible physician/team tends to give the facts only, in the (false) belief that facts are neutral and being as objective as possible is ‘safer’ territory. This is done in a way that does not involve family beliefs and generally does not offer guidance. In this less desirable form of communication, characterized as a one-way conversation, parents are simply made aware of the possible outcomes for their infant’s disorder.

In the preferred mode of communication the aim is to develop a sound parent-physician/team relationship. Here facts need interpretation and judgment, and a deliberate-interactive process (Emanuel and Emanuel 1992) is undertaken in a two-way conversation in which views are shared, and concerns are elucidated, explored, and even challenged at times. Development of a sound, mutually respectful relationship between parents and the healthcare team facilitates discussion of the issues when difficult ethical decisions are required.

3. A Procedural Framework for Ethical Decision-Making

The Principles Underlying Ethical Decision-Making at the Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto are:

- That decisions conform to a standard of judgment that is in the best interests of the child

- That parents’ values and preferences are incorporated in a shared decision-making process

- That consensus be derived between the rightful decision-makers before implementation of a decision

- That medical technical expertise not dominate value

A semi-structured process helps to ensure that the principles listed above and appropriate views and preferences are made explicit. This promotes harmonious decision making, as all of the participants in the process may come to understand the principles, reasons and values underlying a particular choice.

Procedural Framework Steps

1.Determine the Rightful Decision-Makers: A number of individuals may legitimately be involved in a decision making process, including, at least, the parents, the physician with primary responsibility, and other members of the health care team directly involved in the care of that patient. More generally, those who bear the greatest burden of care and conscience, those with special knowledge, and those healthcare professionals with the most continuous, committed, and trusting relationship with the patient and/or parents should be involved in decision-making.

2. Develop Team Consensus: Ensure the rightful team members have had an opportunity to discuss their ethical concerns before embarking on an interaction with the parents. Strong divergence of opinion amongst the team members should not be manifest to the parents.

– Determine who will be taking the lead in the interaction

– Determine which team members need to be present at the meeting with parents: ideally at least two people from different disciplines. The maximum number should be determined as parents can feel overwhelmed by a large number of team members and having their reactions observed during a meeting

3. Create an Optimal Environment for Discussion: e. a quiet and uninterrupted environment in which ethical issues and values can be thoroughly explored

4. Explain the Purpose of the Meeting: Determine whether it is to ensure parental understanding of the clinical situation, to sound out parental views and preferences, to derive a decision or to define that a decision will need to be made at a later stage. Each situation is unique and must be undertaken as such – the unique features of the child, the parents, the condition, and the physician/team.

5. Establish that the Presenting Issue is Indeed an Ethical Problem, one in which moral values conflict or moral uncertainty exists. Ethical deliberation is often complicated by communication problems and psychological issues. These need to be disentangled from the ethical issues.

6. Explain the Concept of Shared Decision Making (SDM): SDM is defined as a collaborative process that allows parents and clinicians to make healthcare decisions together, taking into account the best scientific evidence available, as well as the parents’ values, goals, and preferences (Kon ACCCM and ATS 2016)A shared model of decision-making aims to ensure that the principles of the best interests of the child and respect for parental authority offer coherence in reasoning and an ethically sound guide to action, and that they are harmoniously integrated within the shared decision-making process.Achieving shared decision-making depends on building a good relationship in the clinical encounter so that information is shared and parents are supported to deliberate and express their preferences and views during the decision-making process (Elwyn et al. 2012). Parents should be informed about the essential role they play in decision-making and be given effective tools to help them understand their options and the consequences of their decisions. They should also receive the emotional support they need to express their values and preferences and to be able to ask questions without censure from the clinicians (Barry and Edgman-Levitan).Shared decision-making promotes partnership and communication between clinicians and parents regarding evidence, clinical experiences and parent preferences. (Boland, McIsaac, Lawson).The partnership between clinicians and parents has been shown to improve knowledge, and decrease decisional conflict. (Wyatt KD meta analysis Acad Pediatr 2015)

7. Content of the Discussion: Focus first on the different starting points for parents and physicians (Payot et al. 2007).

Key content factors to address in the encounter include:

- The starting points and the degree of divergence which need to be traversed

- The degree of recognition of the unevenness of the encounter

- The degree of social, cultural, and language divergence

- The degree of empowerment given to parents to express their views

- The actual content (whether generalized or specific)

- How information is contextualized and made personally meaningful and filtered through parents’ own values and beliefs

- The degree of transparency throughout the process of thinking

- The flexibility of all parties

- The involvement of other members of the team or parents’ community and friends.

Establish the relevant facts. ‘Good ethics begins with good facts’. Medical facts include the diagnosis, the prognosis (and the estimated certainty of outcomes), past experience on the clinical unit, relevant institutional policies, and relevant professional guidelines. Non-medical facts include information about family relationships, language barriers, cultural and religious beliefs, and past experiences with the healthcare system. It is also important to ascertain parents’ understanding of the medical facts, their expectations of the technology involved, the quality of communication between the family members, and the degree of trust in physicians, team and the medical system. The willingness of the physician to discuss personal views and beliefs may enhance the gathering of such information.

8. Explore the Options: This entails an explicit discussion of treatment options and their known potential short- and long-term consequences. For physicians, a troubling element at this stage is whether to describe all possible options or only those they consider beneficial. Different physicians perceive their obligations differently. Physicians who feel morally obliged to inform the parents of all possible options should not hesitate, at the same time, to offer a professional recommendation on the course of action considered most appropriate.

9. Negotiate Towards Consensus: All decision-makers should be in agreement with the plan of action proposed at the time, even though, on occasion, agreement may be only on setting another meeting as a temporizing measure.

Open, honest discussion of the goals and consequences of treatment allows parents, physicians, and other legitimate decision-makers to carefully consider a range of professional and personal beliefs, values and preferences, and to then meaningfully explore reasoned arguments for and against various options. This process holds the promise of harmonious, consensual decision-making. The final responsibility does, however, rest with the parents and no decision should be made without their agreement.

If the purpose of the meeting was to negotiate a decision and this cannot be achieved, summarize what has been achieved, describe what needs to be done in the next stage, and set a realistic date for a subsequent meeting.

Document who was present, what was discussed, and the next steps.

The vast majority of complex and difficult ethical decisions result from negotiation, consensus-building and ultimately harmonious agreement between the parents and healthcare professionals as to what is in the child’s best interests. The ideal shared decision is one in which no party feels individually responsible for that decision.

4. Conflict Resolution

Minimizing the potential for conflict is preferable to resolving issues when they have become more divisive and seemingly intractable. The following suggestions are in accord with shared decision-making and conflict-resolution models (Charles et al. 1999; Spielman 1993). These include:

- Ensuring full parental comprehension of the medical information and clarifying any misconceptions and misunderstandings

- Allowing time for further clinical observation and continuing discussion

- Exploring the cultural complexity of the decision-making process

- Clarifying the ethical issues in conflict

- Emphasizing the preferred consensual nature of the decision-making process and shared burden of the decision

- Removing medically or system-imposed obstacles to achieving consensus such as frequent changes in the responsible physician or recognizing the failure of one physician to establish a therapeutic alliance with the parents

- Preventing the development of a ‘contest of wills’ between the physician and parents

- Exploring the degree of (dis)agreement between the parents themselves

- Broadening the parents’ ‘moral community’ by the inclusion of additional family members, significant others, and religious or spiritual advisors in meetings

- Employing creative means to promote ongoing discussion and understanding, such as the use of visual images

- Fostering more private opportunities for the responsible physician to engage in discussion with the parents.

When Parents Say “Do Everything Possible”

At any point in the course of a critically ill patient’s care, parents or families may state that they want “everything done” (Gillis 2008; Feudtner and Morrison 2012; Jecker and Schneiderman 1995). It is important to ask what this really means. Is it a failure to comprehend the prognosis, a lack of confidence in the medical diagnosis or prognosis, a religious belief (often expressed as a belief in miracles) (Kopelman AE 2006), an expression of frustration and alienation, a simple one-liner in a complex situation, or the only available gesture of love and devotion left for the family? Feudtner considers the phrase vague at best and vacuous at worst, and views this as a starting point for a discussion, not an end point (Feudtner and Morrison 2012). Without exploring what underlies a declaration of “do everything,” physicians neglect the complexity of the situation and the unperceived and possibly unexpressed fear of ‘abandonment’ (Cassell 2005).

Parental Insistence on their Role as Final Decision-Maker

Parental insistence on their role and right as final decision-maker may be a valid expression of their perceived role as a parent. I believe, however, that this is usually not their first response. It may be a reaction to ineffective or poor communication, the result of an overly rational approach with a failure to connect to the parental narrative or emotion, or the impact of parents’ stress affecting their ability to absorb information. HCPs also need to recognize that parents often use coping mechanisms of “hope and denial” to interpret data (Cole 2000) and that their understanding may be based more on their own background and beliefs than on the information provided. Their insistence on being the final decision-maker may also result when respect for their role in a shared decision-making process has been disallowed or denigrated.

Intractable Differences

When differences are intractable and the degree of a physician’s moral compromise significant, it may be appropriate to consider transferring responsibility of care of the child to another, accepting physician. If the conflict remains unresolved and if transfer is not a realistic option, physicians may, following ethics consultation, consider seeking institutional or legal advice. However, the impact of such a legal recourse must be seriously considered as it invariably destroys the parent-physician relationship, undermines trust in the medical system, and may increase the anguish for everyone involved (especially the families). In addition, seeking such unilateral authority for decision-making, even in the most extreme circumstances, is regarded by some as not only a clinical failure, but unjustified in principle (Burt 2003). At the Hospital for Sick Children, decisions to withdraw or withhold LSMT are not taken without parental agreement. On rare occasions this may only be tacit agreement in the form of a parent stating they understand why the decision is being made, even if they cannot formally say “they agree,” for fear of the burden of guilt in being party to such a decision.

5. Bioethics Consultation

At times an ethical difference with parents may not be readily resolvable and the Bioethics Department at SickKids may be consulted.

The Department offers a clinical consultation service for hospital staff, patients, families, trainees and students. Any individual may request a consultation: this may be a one-time conversation or it may involve in-depth exploration and long-term strategy development to address the issue(s). Consultations can be individual or group; this is discussed with the individual initiating the request at the time of receiving the consultation (within the limits of the law). At the outset there is a determination that this is in fact an ethical issue

Consultation requests can be made verbally, by email, or telephone. The bioethicist together with the consultee, decide whether further consultation with other individuals is warranted. Confidentiality is preserved until there is a decision to involve others in the process. Should there be a decision not to proceed with a group discussion, the identity of the individual requesting assistance is known only to the bioethicist. This guarantee of privacy, within the limits of the law, is necessary as a reassurance to those seeking assistance from the Bioethics Department.

Bioethics objectives in the usual clinical consultation are to define the values underlying choices, to ensure that the relevant voices are involved in the process, to ensure that a fair process is undertaken, and to elucidate the ethical defensibility of each option, but not to actually make the decision.

The process of consultation regarding such an ethical issue aims to:

- identify the presenting ethical issue(s);

- ensure that all relevant facts, values and options are explored

- consider ethics literature, laws, policy, and contextual factors

- ensure that all benefits and harms of alternative courses of action / inaction are understood;

- facilitate (i.e., assist and guide) decision-making regarding the presenting ethical issue.

Guidelines for Bioethics Consultation

http://policies.sickkids.ca/published/Published/CLINH35/Main%20Document.pdf

During the consultation process, conflict may ensure between stakeholders. Accordingly, the Bioethics Department may reference the policy

Facilitating Conflict Resolution between Parents and the Health Care Team

http://policies.sickkids.ca/published/Published/CLINH31/Main%20Document

Summary

Finding the right balance between respect for parental authority and the physicians’/teams’ role and responsibility in the assessment of child and family interests in a shared decision-making process requires both scientific and humane judgment, empathy, imagination, insight, and effective communication skills. What establishes moral acceptability is not the application of a moral theory or a purely rationalist argument establishing indubitable first principles, but the moral clarity arising out of a mutually derived decision in which all parties have been empowered, their preferences established, and where dialogue and collaboration have (usually) achieved resolution.

Reference

- American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Fetus and Newborn, Bell EF (2007) Non-initiation on withdrawal of intensive care for high-risk newborns. Pediatr 119(2):401-403

- American Medical Association (2010) The AMA code of medical ethics: opinions on seriously ill newborns and Do-not-resuscitate orders. JAMA Ethics 12(7):554-557

- Barry MJ, Edgman-Levitan S (2012) Shared Decision Making – The pinnacle of pPatient centered care. N Eng J Med 366(9):780-781.

- Burt RA (2003) Resolving disputes between clinicians and family about “futility” of treatment. Semin Perinatol 27(6):495-502

- Cassell EJ (2005) Consent or obedience? Power and authority in medicine. N Engl J Med 352(4):328-330

- Charles C, Gafni A, Whelan T (1999) Decision-making in the physician-patient encounter: revisiting the shared treatment decision-making model. Soc Sci Med 49:651-661

- Clark J (2012) Balancing the tension between parental authority and the fear of paternalism in end-of-life care. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 166(7):594

- Conner JM, Nelson EC (1999) Neonatal intensive care: satisfaction measured from a parent’s perspective. Pediatr 103(1):336-349

- Daneman D, Daneman M (2012) What has attachment theory got to do with diabetes care? Diabetes Manag 2(2):85-87

- De Rouck S, Leys M (2009) Information needs of parents of children admitted to a neonatal intensive care unit: a review of the literature (1990-2008). Patient Educ Couns 76(2):159-173

- Downie RS, Macnaughton J (2000) Clinical Judgment: Evidence in Practice. Oxford University Press, New York, p xii

- Dyer K (2005) Identifying, understanding, and working with grieving parents in the NICU, Part 1: Identifying and understanding loss and the grief response. Neonatal Netw 24(3):35-46

- Elwyn G, Frosch D, Thomson R et al (2012). Shared decision making: A model for clinical practice. J Gen Intern Med 27(10):1361-7

- Emanuel EJ, Emanuel LL (1992) Four models of the physician-patient relationship. JAMA 267(16):2221-2226

- Feltman DM, Du H, Leuthner SR (2012) Survey of Neonatologists’ attitudes toward limiting life-sustaining treatments in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit. J Perinatol 32(11):886-892

- Feudtner C, Morrison W (2012) The darkening veil of do everything possible. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 166(8):694-695

- Gillis J (2008) We want everything done. Arch Dis Child 93(3):192-193

- Hardart GE, Truog RD (2003) Attitudes and preferences of intensivists regarding the role of family interests in medical decision making for incompetent patients. Crit Care Med 31(7):1895-1900

- Hardwig J (1990) What about the family? Hastings Cent Rep 20(2):5-10

- Harrison C (2004) Treatment decisions regarding infants, children and adolescents CPS Statement. Pediatr Child Health 9(2):99-103

- Harrison C Personal communication

- Harrison H (1993) The principles for family-centered neonatal care. Pediatr 92(5):643-650

- Hester DM (2007) Interests and neonates: There is more to the story than we explicitly acknowledge. Theor Med Bioeth 28:357-372

- Heyland DK, Rocker GM, Dodek PM et al. (2002) Family satisfaction with care in the intensive care unit: results of a multiple center study. Crit Care Med 30(7):1413-1418

- Holm S, Edgar A (2008) Best interests: A philosophical critique. Health Care Anal 16:197-207

- Jecker NS, Schneiderman LJ (1995) When families request that ‘everything possible’ be done. J Med Philos 20:145-163

- King NM (1992) Transparency in neonatal intensive care. Hastings Cent Rep 22(3):18-25

- Kopelman AE (2006) Understanding, avoiding, and resolving end-of-life conflicts in the NICU. The Mt Sinai J Med 73(3):580-586

- Kopelman LM (2005) Rejecting the Baby Doe rules and defending a “negative” analysis of the best interest standard. J Med Philos 30:331-352

- Kopelman LM, Kopelman AE (2007) Using a new analysis of the best interests standard to address cultural disputes: whose data, which values? Theor Med Bioeth 28(5):373-391

- Ladd RE, Mercurio MR (2003) Deciding for newborns: whose authority? whose interests? Semin Perinatol 27(6):488-494

- Marcello KR, Stefano JL, Lampron K et al (2011) The influence of family characteristics on perinatal decision making. Pediatr 127:e934-e939

- McHaffie HE, Laing IA, Parker M et al (2001) Deciding for imperiled newborns: medical authority or parental autonomy? J Med Ethics 27:104-109

- Mitchell C (1984) Care of severely impaired infant raises ethical issues. Am Nurse 16: 9

- Montello M, Lantos J (2002) The Karamazov complex: Dostoevsky and DNR orders. Perspect Biol Med 45: 190-9

- Moore KAC, Coker K, DuBuisson AB et al (2003) Implementing potentially better practices for improving family-centered care in Neonatal Intensive Care Units: Successes and challenges. Pediatr 111(4):e450-e460

- Paris JJ, Graham N, Schreiber MD et al (2006). Has the emphasis on autonomy gone too far? Insights from Dostoevsky on parental decision-making in the NICU. Camb Q Healthc Ethics 15:147-151

- Paris JJ, Schreiber MD, Moreland MP (2007) Parental refusal of medical treatment for a newborn. Theor Med Bioeth 28:427-44

- Payot A, Gendron S, Lefebvre F et al (2007) Deciding to resuscitate extremely premature babies: how do parents and neonatologists engage in the decision? Soc Sci Med 64:1487-1500

- Racine E, Shevell MI (2009) Ethics in neonatal neurology: When is enough, enough? Ethics Neo Neurol 40(3):147-155

- Spielman BJ (1993) Conflict in medical ethics cases: seeking patterns of resolution. J Clin Ethics 4(3):212-218

- Truog RD, Sayeed SA (2011) Neonatal decision making: beyond the Standard of Best Interests. Am J Bioeth 11(2):44-45