Drug Intoxication, Abstinence and Withdrawal Syndromes

Doug Campbell MSc, MD, FRCPC

The material presented here was first published in the Residents’ Handbook of Neonatology, 3rd edition, and is reproduced here with permission from PMPH USA, Ltd. of New Haven, Connecticut and Cary, North Carolina.

General Complications of Illicit Drug Use in Pregnancy

- Miscarriage

- Placental abruption

- Placental insufficiency

- IUGR

- Stillbirth

- Preeclampsia and eclampsia

- Premature labour, PROM

- Asphyxia

- Neonatal withdrawal and/or neurotoxicity

- Smoking exposure continues to be a major contributor to low birth weight, stillbirth, prematurity and increased SIDS

- Alcohol continues to be the most common prenatal exposure; can be teratogenic and lead to permanent neurologic sequelae

- Mixed exposure very common making it difficult to understand independent short and long-term effects of most common illicit drug exposure (cocaine, amphehtamine, opiods, cannabis, ectasy, etc)

Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder (FASD)

FASD is an umbrella term describing the range of effects that can occur in an individual whose mother drank alcohol during pregnancy. These effects may include physical, mental, behavioural and learning disabilities with lifelong implications.

FASD is not a diagnostic term per se; Fetal Alcohol Syndrome (FAS) is the most visible presentation and requires the presence of: characteristic facial features, prenatal and/or postnatal growth restriction (including micxrocphaly), and developmental delays. There are a number of FASD-related disabilities, most of which are missed in the neonatal period and diagnosed in childhood or adolescence. No amount of alcohol exposure is safe but there is a general dose-response relationship.

Cannabis

- When considering women of childbearing age (15-44 years), approximately 11% reported past-year cannabis use.

- According to data from national surveys in the United States, just over 5% of pregnant women aged 15-44 reported cannabis use in the previous month.

- Specifically, in inner city populations, 23-30% of individuals reported using cannabis during pregnancy.

- 5-fold increase in distorted facial features compared to FASD babies, mixed data on fetal growth effects.

Cannabis and breastfeeding

- The evidence that cannabis is neurotoxic to the neonate via exposure in breast milk is poorly understood, best to think of it as a ‘relative contraindication’.

- THC concentrates in breastmilk – THC fat soluble, can be present for long periods of time, THC levels are increasing in modern forms of marijuana, edibles, etc and not always regulated.

- Presence of other toxins found in marijuana is also concerning.

- Multiple longitudinal studies have described effects on long-term neurocognitive functioning and behavioural changes in heavy maternal users (while pregnant).

- In the absence of significant data, efforts should be focused on reducing, quitting, and discouraging use (harm reduction).

- There is some emerging evidence that recreational users may not have large amounts of THC in their breastmilk. More research needed to understand true risks of breastfeeding, actual exposure of THC via breastmilk and its relationship to neurodevelopment outcome relative to fetal exposure to cannabis.

Selective Serotonergic Reuptake Inhibitiors (SSRI) exposure

Depression and other mental health disorders in pregnancy can have well recognized severe effects on the fetus: including growth restriction, premature delivery, and fetal loss. Minimal fetal risks to SSRI exposure occur when used with good prenatal care providers.

- Neonatal behavioral syndrome, especially with late SSRI, and related compounds (SNRI, NaSSA,etc) is often now termed ‘Serotonergic reuptake inhibitor related-syndrome’.

- Symptoms can be seen in up to 10-30% of newborns and are usually self-limiting to 48 hours: tremors, jitteriness, feeding dysregulation, weak cry.

- PPHN possible but not consistently proven to be increased with SSRI use.

- Long-term neurodevelopmental outcome not clearly affected.

Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome (NAS)

NAS is a constellation of symptoms that arise after abrupt discontinuation of a exposure to maternal substances, primarily this refers to opioid exposure.

Physiology

- Removal of opioid stimulation causes superactivation of the cellular adenyl cyclase cascade system, eventually inducing a surge of neurotransmitters (norepinephrine & acetylcholine) and decreased dopamine & serotonin.

- High density of opioid receptors within the central nervous and gastrointestinal systems accounts for resulting symptoms

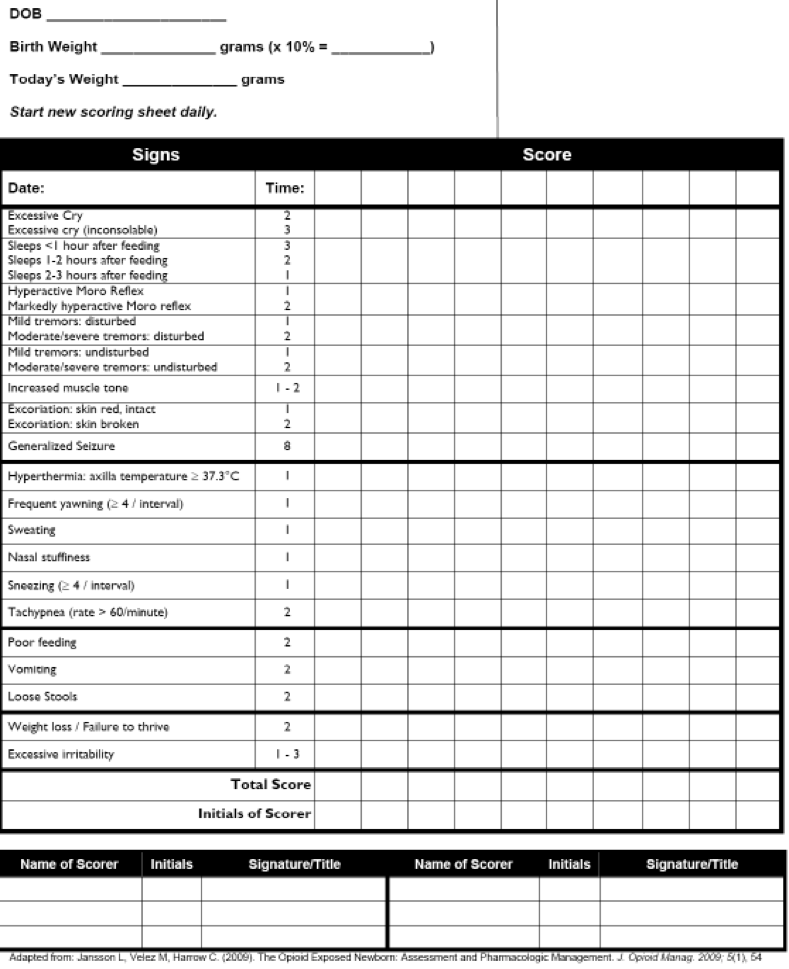

General Classification of symptoms (Figure 1)

| Symptoms | |

|---|---|

| CNS | Excoriation Hyperactive reflexes Increased muscle tone Irritability, excessive crying Jitteriness, tremulousness, myoclonic jerks Seizures Sleep disturbance |

| Autonomic Dysfunction | Excessive sweating Excessive yawning Hyperthermia |

| Respiratory Symptoms | Stuffiness, sneezing Tachypnea |

| GI/Feeding | Poor intake/excessive eating Weight Loss Diarrhoea Excessive sucking Regurgitation |

Factors affecting timing of neonatal symptoms

- The opioid/poly-substance itself

- The timing of the most recent use by the mother prior to delivery

- Maternal metabolism

- Transfer of drug across placenta

- Infant Metabolism

- Short acting

- Fentanyl: (6-12 hours after birth)

- Heroin: symptoms may appear in first 24 hours, if used shortly before birth

- Longer acting

- Methadone: symptoms within 120 hours

- Suboxone (Buprenorphine-naloxone): symptoms within 5-7 days

- Subutex (Buprenophrine): 2-5 days

Emerging evidence that maternal use of buprenorphine c/w methadone offers advantages to neonates: lower total doses of morphine required and decreased length of stay.

Epidemiology of NAS

- 1-5% of Canadian women report illicit drugs use during pregnancy

- 3.8 out of 1000 births were to mothers using opioids during pregnancy Increased stillbirth rate (11.4/1000 births) and infant mortality rate also reported(12/1000 live births)

- 0.3% of all babies born in Canada 2009-2010 were diagnosed with NAS

- Withdrawal will occur in 85% of methadone exposed infants and 55-94% of infants exposed to other opioids Mean LOS 14 days, cost per infant $12,917.00 (US 17 days, $66,000/infant)

Scoring – Modified Finnegan Tool (Figure 2)

| NAS Score | PO Equivalent | IV equivalent dose |

|---|---|---|

| 8-10 | 0.32 mg/kg/day | 4.5mcg/kg/hr |

| 11-13 | 0.48 mg/kg/day | 6.7mcg/kg/hr |

| 14-16 | 0.64 mg/kg/day | 8.9mcg/kg/hr |

| 17+ | 0.80 mg/kg/day | 6.7mcg/kg/hr |

Treatment of NAS

Non-pharmacologic

- prenatal support, addiction counseling

- recognition of trauma, trauma-informed support by multidisciplinary team

- build trust

- develop plan including breastfeeding plan if possible

- Environmental support of family if possible including: rooming-in program, quiet environment, promotion of skin-to-skin, swaddling, music & sound therapy

- consistent caregivers

- involve families in the care

Pharmacologic

Morphine replacement as soon as possible if symptoms are noted. Escalate morphine dose by increasing daily dose and adding breakthrough doses. Severe symptoms of NAS may require IV morphine use for quicker resolution of symptoms.

- Weaning begins once abstinence scores are stable (usually less than 8) for at least 24 hours.

- Wean 10-20% daily dose every 2-4 days (may take weeks)

Adjunctive pharmacological treatment

Use of morphine in NAS (Figure 3)

Clonidine

- Alpha 2 receptor agonist, inhibits sympathetic flow pre-synaptically

- Used in conjunction with morphine

- If unable to stabilize well with morphine as single agent

- Usually if total dose > 1mg/kg/day

- Dosing guidelines:

- Preterm 0.5-1 mcg/kg/dose q6h

- Full term 1 mcg/kg/dose q6h **

- Give with feeds

- Adverse effects: hypotension, bradys, tachy, drowsiness/sedation, rash, constipation

Long term consequences of NAS

- Australian study followed kids until high school entry. Children with NAS treated in NICU matched by GA and SES followed through Grade 3, 5 and 7 standardized testing scores.

- NAS associated independently with poor and deteriorating school performance.

- Effect mitigated somewhat by parental education

Phenobarbital

- GABA agonist agent

- Not recommended for NAS treatment, but may be useful in treatment of neonates having withdrawal from polysubstance use exposure

References

- Kirpalani, H., Moore, A.M. and Perlman, M., 2007. Residents handbook of neonatology. PMPH-USA

- SOGC statement on pregnancy and lactation 2017 – http://www.ccsa.ca/Resource%20Library/CCSA-Cannabis-Maternal-Use-Pregnancy-Report-2015-en.pdf

- ACOG statement Number 722, October 2017

- Brogly SB et al. Infants born to opioid dependent women in Ontario 2002-2014. JOGC 39(3):157-165.

- McQueen K et al. Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome. NEJM 2016;375(25):2468-2479.

- Kocherlakota P. Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome. Pediatrics 2014;143(2):e547-e561.

- Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse (CCSA) 2017. http://www.ccsa.ca/Resource%20Library/CCSA-Canadian-Youth-Perceptions-on-Cannabis-Report-2017-en.pdf

- Newman A et al. Can Fam Physician 2015;61:e555-61

- Dow K et al, NAS clinical practice guidelines for Ontario. J Popular Ther Clin Pharmacol. 2012;19(3):e488-506.

- Finnegan LP. Neonatal abstinence. In: Nelson NM, ed. Current Therapy in Neonatal–Perinatal Medicine. 2nd ed. Toronto, Ontario: BC Decker Inc; 1990

- Oei JL et al. NAS and High School Performance.Pediatrics 2017;139(2):e2651

- Moses-Kolko EL et al JAMA 2005;293:2372-2383.

- Sie SD et al. Maternal use of SSRIs,. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2012;97:F472–F476.

- Chudley A et al. Fetal alcohol spectrum disorder: Canadian guidelines for diagnosis. CMAJ. 2005 Mar 1; 172(5 Suppl): S1–S21. doi: [10.1503/cmaj.1040302]