Gastrointestinal Disorders

Aideen M Moore MD, FRCPC, MRCPI, MHSc and Carlos Zozaya, MD

The material presented here was first published in the Residents’ Handbook of Neonatology, 3rd edition, and is reproduced here with permission from PMPH USA, Ltd. of New Haven, Connecticut and Cary, North Carolina.

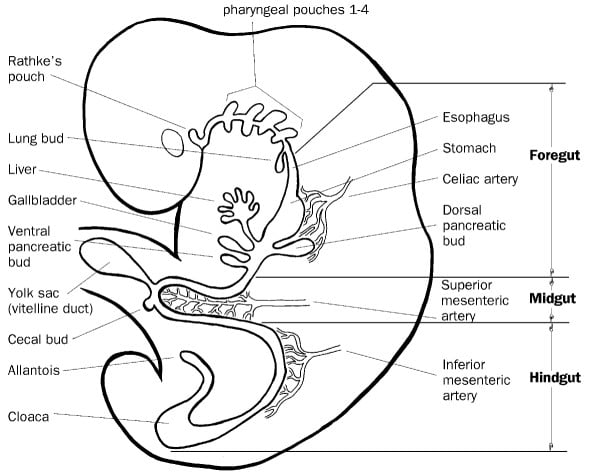

Chronology of Gastrointestinal Development

4 weeks Gastrointestinal tract formed by invagination and folding of the embryo

20 weeks Morphologically mature gut, appearance of non-nutritive sucking

20-26 weeks Digestive and absorptive function increases

32-34 weeks Abrupt rise in lactase activity

34 weeks Mature sucking and swallowing

40 weeks Mature migrating motor complexes

Postnatal Further maturation of gastric emptying, acid production and digestion

Gastrointestinal (GI) disorders that can present in Utero are listed in Table 1.

Table 1. Disorders of GI Function in Utero

Symptom |

Underlying Cause |

Clinical Sign |

| Inability to swallow | -Obstructive lesions (mouth to lower esophagus), -CNS disoders, myopathies |

Polyhydramnios |

| Vomiting | Obstructive lesions of stomach/duodenum | Polyhydramnios ± bile-stained amniotic fluid |

| Diarrhea | Congenital enteropathy | Polyhydramnios |

| Meconium passage | Stress of asphyxia – very rare in preterm infant, consider Listeria infection |

Meconium staining |

Clinical Background

Postnatal adaptation of the GI tract is not always smooth. Even healthy term infants commonly have reflux, but more serious problems are likely in the very preterm infant. In addition, a number of serious congenital anomalies of the gastrointestinal tract present in the first few days of life (also see Surgery chapter). Postnatal adaptation of the gastrointestinal tract can be maximized by early feeding.

Specific problems of preterm infants, mainly with respect to control of GI motility, include:

1. Incoordination of swallowing with breathing, <34 wk gestation

2. Poor control of gastroesophageal reflux

3. Delayed gastric emptying causing increased aspirates and feeding intolerance

4. Decreased intestinal motility, resulting in feeding intolerance; mature motility is only seen at 32-36 weeks

5. Delayed evacuation of meconium and stools

Abdominal Distension

Causes of abdominal distension at birth and their initial management are listed in Table 2.

Table 2. Causes of Abdominal Distension at Birth

Disorder |

Initial Management |

| Gaseous Distension Bag and Mask ventilation CPAP |

Plain/ lateral radiograph of abdomen Open-ended nasogastric tube to decompress stomach |

| Congenital ascites Urinary tract obstructions Hydrops of any cause Chylous ascites |

Paracentesis Abdominal ultrasonography |

| Congenital bowel obstruction /perforation Volvulus / malrotation Meconium ileus Small bowel atresias Hirschprung’s disease |

Plain radiograph of abdomen-AP and cross-table lateral GI contrast study particularly for meconium plug Surgical consultation |

| Congenital abdominal masses Massive renal anomalies Cystic lesions of liver, mesentery, ovary etc. Rare tumors |

Abdominal ultrasonography |

Abdominal Distension with Vomiting and Delayed Meconium Passage

1. Passage of meconium normally occurs within 24 hours of birth in term infants. Rectal stimulation or a glycerine suppository may resolve delayed meconium passage in some normal infants.

2. Lower GI obstructions cause abdominal distention, delayed meconium passage, and vomiting, usually not bile-stained.

3. Upper GI obstructions cause upper abdominal distention and vomiting which is usually bile-stained; some meconium passage may occur.

Major Causes of Abdominal Distension

Imperforate anus. Inspection of the perianal region reveals abnormal anatomy – this is considered part of the normal newborn examination. Fistulas to the perineum or genitourinary tract should be looked for carefully, present in 80-90% cases, but may take 24 hours to declare. The lesion may be high or low (above or below the levator ani). Surgical correction is usually required. Of patients with imperforate anus, 50-60% have other defects, especially the VACTER association of anomalies (vertebral defects, imperforate anus, cardiac, TEF, and radial and renal dysplasia).

Meconium plug. Meconium plug is usually benign and is associated with prematurity, intrauterine growth restriction and hypothyroidism. Rarely Hirschprung’s disease, small left colon, or meconium ileus present as meconium plug. Contrast enema is usually diagnostic and therapeutic. Infants should also be screened for CF by DNA testing and sweat chloride.

Hirschprung’s disease. Also called congenital aganglionic megacolon, it is a common cause of neonatal intestinal obstruction. The aganglionic segment may be limited to the rectosigmoid colon or extend proximally to involve the entire colon or small intestine. Diagnosis is suggested by abdominal films and contrast enema and confirmed by rectal biopsy. Colostomy is usually required, followed by definitive repair at 8 to 12 months of age.

Microcolon. Demonstrated by contrast enema. Seen in infants of diabetic mothers and in association with ileal atresias, meconium plug syndrome and Hirschprung’s disease.

Paralytic ileus. Causes include sepsis, asphyxia, gastroenteritis, severe pulmonary disease, electrolyte imbalance (hypokalemia, hypercalcemia, hyperammonemia), and drugs (pancuronium or other muscle relaxants).

Peritonitis. Peritonitis is usually secondary to perforation. Radiographs in the decubitus and a cross-table view should be obtained. CBC, differential and blood cultures should be taken and broad spectrum antibiotics started. Perforations are usually of small or large bowel, but can be isolated to the stomach.

Necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC). See below.

Small bowel atresia or stenosis. Duodenal or high jejunal atresia characteristically present as a “double-bubble” on plain radiograph of abdomen. Ileal atresias may be multiple.

Meconium ileus. Meconium ileus may present as volvulus, malrotation, “frog-spawn” gas pattern on radiograph, or peritoneal calcification secondary to in-utero perforation. Exclude cystic fibrosis by DNA testing and sweat chloride.

Volvulus, duplication, or malrotation. These conditions may cause intermittent symptoms and signs and are often missed. Midgut volvulus is one of the most serious emergencies seen in the newborn period, as delay in diagnosis may result in significant bowel loss with resultant morbidity and mortality. If suspected, urgent surgical opinion and contrast studies are required (also see Surgery Chapter).

GI obstructions presenting later. Pyloric stenosis usually occurs within the first 3-6 weeks of life, but may be delayed in preterm infants. Diagnosis is confirmed by finding an ‘olive’ on abdominal palpation or by ultrasound examination. Fluid and electrolyte abnormalities (hypochloremic alkalosis) need to be corrected prior to surgery.

Post-NEC stricture. Stricture formation is usually antedated by a clear-cut episode of NEC. Distension and vomiting may be intermittent and vague. Confirmed by contrast studies. May resolve spontaneously, but surgery usually required.

Incarcerated hernia. Hernia is usually easily recognized clinically. Surgery is required for irreducibility or incarceration. For preterms, the hernia should be fixed before discharge, or when the infant is off supplemental oxygen.

Necrotising Enterocolitis (NEC)

Necrotising Enterocolitis (NEC) an inflammatory disorder of the intestine, usually seen in premature infants. It involves coagulation necrosis, bacterial overgrowth, inflammation and in severe cases necrosis of the bowel wall. It is a major cause of death and morbidity in neonates.

Incidence: The overall incidence of NEC is 1-7% of all admissions to an NICU. 90% of infants are preterm, with greater risk at lower gestational age. If perforation occurs, mortality approaches 40%. In term infants the main risk factors are congenital heart disease, perinatal asphyxia, intra-uterine growth restriction and polycythemia.

Multifactorial Aetiology: The underlying pathogenesis of NEC is not completely understood, current evidence suggests a multifactorial aetiology.

- Prematurity (seen in 90%) is the most important risk factor. The incidence of NEC is inversely proportional to the gestational age at birth. Immaturities in intestinal barrier function, gastric acid production, motility, some digestive enzymes and an imbalance in the inflammatory response may contribute to NEC

- Abnormal intestinal microbiota, either from a lack of beneficial commensal microbes, a low diversity of bacteria or a preponderance of pathogenic bacteria

- Ischemia re-perfusion injury; many risk factors involve decreased mesenteric perfusion and intestinal ischemia e.g. intrauterine growth restriction, perinatal asphyxia, congenital heart disease and patent ductus arteriosus

- The use of formula instead of breast milk increases the risk of NEC. Older studies suggested rapid advancement of enteral feedings was associated with an increased risk of NEC, however recent meta-analyses have not shown an effect of aggressive feeding or delayed initiation of enteral feeding on NEC

Clinical Presentation

- NEC usually presents at 2-3 weeks of age, earlier in more mature infants and with a range of 1-12 weeks.

- Gastrointestinal signs include abdominal distension, bile-stained gastric aspirates and bloody stools (haematochezia).

- Systemic signs are common and include lethargy, temperature instability, increased frequency of apnoea and bradycardia and poor perfusion which may progress to shock.

Diagnosis of NEC

Diagnosis of NEC is based on presenting signs, laboratory tests and radiological or surgical findings. Definitive diagnosis is the finding of intramural gas (pneumatosis intestinalis) on abdominal X-ray. Some centres have started to include abdominal ultrasonography in the evaluation of NEC. The terminal ileum and ascending colon are most often affected, but in severe cases it can involve the whole gastrointestinal tract. Gas may be detected radiologically, ultrasonographically, at operation, or histologically.

Radiological Findings

Findings (AP and cross-table lateral) include:

1. Questionable NEC (Bell’s Stage I):

- Thickened bowel wall

- Fixed-position loops on serial films

- Ascites

2. Definite NEC:

- Intramural gas (pneumatosis intestinalis) is caused by hydrogen production from pathogenic bacteria.

- Portal gas

- Free air

3. Perforated NEC, with free air in the abdominal cavity.

Bowel Necrosis

Bowel necrosis is inferred clinically from severity of systemic illness, including shock, persistent thrombocytopenia, GI bleeding and abdominal signs (evidence of ileus, tenderness, abdominal wall inflammation, right lower quadrant mass). Some authorities have used paracentesis to determine indications for surgery. Isolated focal intestinal perforation, in the absence of NEC, is also recognized but appears to have a better prognosis.

NEC Regimen

The following outline details the recommended regimen:

1. Full septic work-up:

Complete blood count and differential

Monitor blood gases, glucose, electrolytes, BUN and creatinine

Cultures of blood, urine, stool (bacterial and viral), and CSF (latter when stable)

2. Strictly nil by mouth

3. Nasogastric tube open-ended

4. IV fluid resuscitation; correct acidosis and hypoperfusion, anticipate increased fluid requirements because of third spacing

5. Blood products may be needed to correct thrombocytopenia, coagulopathy or anaemia

6. Ventilatory support may be required for apnoea or increasing acidosis

7. Broad-spectrum antibiotics; antibacterial choice is governed by culture results:

I.V. ampicillin and gentamicin (vancomycin and gentamicin if NEC occurs after 1 week of life)

Routine anaerobic coverage has not been shown to be of benefit however, it is recommended in severe cases involving perforation. Consider adding antifungal therapy if patient is not responding to antibiotic. Antibiotics are usually continued for 7-10 days for uncomplicated NEC and approximately 14 days for severe or perforated NEC, however there is a lack of good evidence on duration of antibiotic coverage

8. Start parenteral nutrition as soon as possible, ensure good intravenous access, likely to need central line

9. Serial radiographs every 6 hours for the first 24hours, or while patient is clinically unstable

10. Surgical consultation for definite NEC

Duration of ‘NEC Regimen’ is based on clinical staging, see Table 3

Table 3. Duration of Necrotizing Enterocolitis Treatment Regimen According to Modified Bell’s Staging Criteria

Manifestation |

Treatment |

| Suspected NEC (Stage I) | |

| “Suspected sepsis” plus mild GI symptoms but no blood in stool or intramural gas | NPO, antibiotics × 3 d, pending cultures |

| AXR may be normal or show mild ileus | |

| Definite NEC (Stage II) | |

| Presence of intramural gas(pneumatosis intestinalis); intestinal dilatation, ileus | NPO, antibiotics × 7–14 d, depending on severity of illness |

| Advanced NEC (Stage III) | |

| Definite NEC plus complication (e.g., acidosis, shock, thrombocytopenia, coagulopathy, portal vein gas, evidence of localized or early peritonitis, ascites) | NPO, antibiotics × 10–14 d Likely to require fluid resuscitation, blood products, inotropic and ventilatory support |

| Perforated NEC | Same as above, minimum 14d plus surgical intervention |

Indications for surgery are:

1. Free intraperitoneal air on abdominal radiograph

2. Relative indications include intractable metabolic acidosis, abdominal mass or ‘fixed loop’ on abdominal X-ray

Surgical Management of NEC

- The main principles of surgery are intestinal decompression, resection of necrotic bowel, and formation of a stoma. Primary closure may be considered for localized disease.

- Peritoneal drainage may allow stabilization in critically ill infants and later surgical intervention if required.

Sequelae

1. Recurrent NEC, intestinal necrosis, perforation

2. Post-NEC bleeding due to strictures

3. Strictures, which occur in about 10% of cases, and are mostly located in large bowel; if symptoms persist, barium enema should be performed

4. Short-bowel syndrome is likely if >50-75% of small intestine is lost

5. Liver cirrhosis secondary to prolonged total parenteral nutrition

6. Dumping syndrome

Differential Diagnosis

1. Septic ileus

2. Isolated gastric or intestinal perforation

3. Bowel obstruction (eg, malrotation with mid-gut volvulus, intussusception)

4. Infectious enterocolitis

5. Feeding intolerance, poor bowel motility

Long-term Outcome

- The overall survival is 60-70%

- Intestinal adaptation may occur over the first 2 years

- A significant number of survivors show developmental delay, hence close neurodevelopmental follow-up should be arranged.

Prevention of NEC/ future directions

- Promote breast milk feedings and advance feeds at rates <20mL/kg/day. (there is a swing back to utilization of banked breast milk – see Chapter)

- Oral immunoglobulins are not recommended based on the available evidence.

- Oral antibiotics may reduce the incidence of NEC, however concern about the development of resistant bacteria precludes widespread use.

- The use of probiotics as well as arginine supplementation is being evaluated

Feeding Intolerance

Difficulty in initiation of feeds, and or increasing feed volumes, is common in extremely low-birth-weight infants. The underlying cause is thought to be immaturity of GI motility, especially of gastric emptying.

Diagnosis (see also Nutrition and Feeding Chapter)

- Excessive gastric residuals (aspirates), >1mL/kg or >50% of previous feeding, whichever is larger, in two out of three consecutive feeds

- Abdominal distension (>2 cm in abdominal girth, over the previous measurement)

- Positive occult blood in stool may be present

Table 4. Feeding Intolerance

Definition |

Differential Diagnosis |

| Gastric aspirate >50% of previous feeding | Immature GI motility |

| Abdominal girth increase >2 cm | Reflux |

| Vomiting or diarrhea | Septic ileus |

| NEC | |

| Bowel obstruction (e.g., malrotation with midgut volvulus, intussusception) |

|

| Infectious enterocolitis | |

Management

1. Hold feeds while infant is being assessed.

2. Depending on clinical severity, consider abdominal radiograph, CBC and diff and blood gas to exclude NEC or mechanical causes of abdominal distension (see above).

3. Reintroduce feeds slowly and consider alternative feeding strategies, such as slow bolus or continuous feeds or decreased volumes and less frequent feeds.

4. Consider pharmacological therapy.

5. Cisipride is now contraindicated in premature infants because of prolonged QT interval.

6. Erythromycin, a motilin agonist, may be of benefit especially in older prems, >32 weeks

7. There is evidence that metoclopramide decreases the gastric emptying rates in preterm infants although use is limited because of adverse effects.

Prevention

Early introduction of “minimal enteral nutrition” enhances maturation of intestinal motor patterns and release of GI hormones, without increasing the incidence of NEC.

Gastroesophageal Reflux in the Neonate

Gastroesophageal reflux (GER) is the retrograde movement of gastric contents into the oesophagus and above due to decreased lower oesophageal sphincter tone. While GER can be physiologic in healthy thriving infants, it is more frequently associated with symptoms of disease in infants < 1500g. Acid reflux has the potential to cause injury of the oesophageal mucosa and oesophagitis.

Clinical features vary from simple regurgitation to vomiting of feeds to the association of GER with apnoea and bradycardia and aspiration.

Management

1. Avoid precipitating factors, e.g. frequent suctioning

2. Positioning: prone or left lateral

3. Dietary Changes

– Thickening of feeds has been shown to be of benefit in term infants but data is lacking for preterms

4. Prokinetic agents act on regurgitation through their effects on lower oesophageal sphincter pressure, esophageal peristalsis or clearance or by increasing gastrointestinal motility. No ideal pharmacologic agent exists for infants.

5. Acid reduction to prevent inflammation of the lower oesophagus using H2 blockers or proton pump inhibitors. Should be used sparingly as increase infection rates and alter the microbiome.

Gastrointestinal Bleeding

Differentiate between upper and lower GI bleeding by placing NG tube and aspirating. Recovery of blood from the stomach is diagnostic of an upper GI bleed. Gastrointestinal bleeding is not uncommon, but the cause often remains unknown

Table 5. GI Bleeding

| Upper GI Bleeding | Lower GI Bleeding |

| Nasogastric tube irritation Swallowed maternal blood Gastritis/ Stress ulcers Portal hypertension Coagulopathy, DIC Vitamin K deficiency |

Anal fissure Necrotizing enterocolitis Volvulus/Malrotation* Meckel’s Intusscusception Allergic coloitis |

| * If bleeding from malrotation with midgut volvulus is suspected, prompt laparotomy is indicated | |

Upper GI Bleeding

1. Nasogastric tube irritation. This is the most common cause of GI bleeding, and is usually trivial.

2. Swallowed maternal blood (spurious GI bleeding) during delivery or from bleeding from nipple. An Apt test (on gastric aspirate/stool) identifies maternal blood, and is diagnostic. No treatment required. In an Apt test 1 volume of vomitus or stool is mixed with 5 volumes of water. The mixture is centrifuged briefly and 4 mLs of the supernatant (hemolysate) is mixed with 1mL 1% NaOH. Fetal hemoglobin (Hbg F) will remain pink, while maternal blood (Hbg A), changes from pink to a yellow-brown colour.

3. Gastritis / stress ulcers. This is the most common cause of severe GI bleeding and hemorrhage can be severe.

4. Severe perinatal asphyxia and hypovolemic shock are often lethal when associated with GI complications.

5. Portal hypertension. Rare in the newborn, seen in end stage liver disease.

6. Hemorrhagic disease of the newborn. Seen in infants who did not receive vitamin K at birth or whose mothers took medications that interfered with vitamin K. Causes generalised bleeding, including hematemesis, hematuria and prolonged bleeding at venipuncture sites. Treatment is to give vitamin K, 1mg daily for 5 days, preferably by IV for active bleeding

Lower GI Bleeding

1. Anal fissure. Is the most common cause of lower GI bleeding. Bright red blood is seen on the surface of the stool or on the diaper. Confirmed by examining anus. Treatment is to ensure that stool is soft and to apply a protective ointment to allow healing.

2. Necrotizing enterocolitis. This condition is usually, but not always associated with minor GI bleeding, usually from the lower GI tract.

3. Malrotation and midgut volvulus. Volvulus may result in infarction of the midgut due to obstruction of the mesenteric blood supply. Abdominal tenderness or melena in association with bilious vomiting, suggests vascular compromise and requires urgent surgical intervention.

4. Meckels diverticulum. Bleeding results from heterotopic gastric mucosa. Rare in neonates, diagnosis usually made on Meckel’s scan.

5. Intussusception. Rare before 3 months. Diagnosis made by abdominal radiography, ultrasonograpy and contrast enema.

6. Allergic colitis. Cow’s milk or rarely soy protein allergy. Treatment is to exclude the precipitating factor, e.g. by using a protein hydrolysate formula

Management of GI bleeding

1. In severe hemorrhage replace blood loss with fresh whole blood

2. Correct coagulation deficiencies

3. For gastritis use nasogastric suction, saline lavage and H2 blockers (Ranitidine by i.v. infusion, 500 micrograms/kg once every 6 hours or with minor bleeding i.v. q6-12h), to keep gastric pH > 5).

4. Gastroscopy and/or surgery is rarely required (yet consider when blood replacement is > 50% of blood volume.

Additional Reading

- Kirpalani, H., Moore, A.M. and Perlman, M., 2007. Residents handbook of neonatology. PMPH-USA

- Neu J, Walker WA. Necrotizing enterocolitis. N Engl J Med 2011;364:255-64.

- Patel RM, Denning PW. Intestinal microbiota and its relationship with necrotizing enterocolitis. Pediatr Res 2015;78:232-238.

- Bell MJ, Ternberg JL, Feigin RD, Keating JP, Marshall R, Barton L, Brotherton T. Neonatal necrotizing enterocolitis. Therapeutic decisions based upon clinical staging. Ann Surg 1978;187:1-7.

- Morowitz MJ, Poroyko V, Caplan M, Alverdy J, Liu DC. Redefining the role of intestinal microbes in the pathogenesis of necrotizing enterocolitis. Pediatrics 2010;125: 777–785.

- Walsh MC, Kliegman RM. Necrotizing enterocolitis: treatment based on staging criteria. Pediatr Clin North Am 1986;33: 179–201.

- Neu J, Zhang L. feeding intolerance in very-low-birthweight infants: What is it and what can we do about it? Acta Paediatrica 2005;94(Suppl 449):93-99.

- Eichenwald EC and AAP Committee on fetus and newborn. Diagnosis and management of gastroesophageal reflux in preterm infants. Pediatrics 2018;142(1):e20181061